June 29, 2013

Welcome to the next chapter of “Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance, Health & Life”, in which I'm going to give you 7 of the best weapons to beat stress – a hidden killer that completely sabotages your recovery.

Stress is the #1 thing that I've found to completely sabotage anyone's pursuit of better performance, recovery or physique, but today you are going to discover what stress does to your mind-body connection, how that mind-body connection works, and then exactly what you need make that mind-body connection 100% bulletproof.

Let's begin with a story.

Way back in Chapter 3, I talked about how Mark Sisson gives an excellent perspective on the conundrum of stress and endurance training in his book “The Primal Connection” – in which he describes how a major factor at play in the success of some pro endurance athletes is relatively lower amounts of work stress, deadlines, office obligations, etc. in the life of those who are able to devote most of their time to training.

Here’s how Mark describes his experience coaching a team of world-ranked professional triathletes, and comparing their lives to that of the amateur triathlete:

“The typical amatueur triathlete was a type-A overachiever with a demanding career and a busy family life. Fitting in the requisite workouts was a constant juggling act between work and family obligations. The word “squeeze” was used repeatedly to describe scheduling efforts, starting with the morning alarm and an abrupt commencement of the day’s first workout. Pacing seemed to be an obsession, not just for tracking workout speed, but minding the clock at all times in order to remain “on time” for every item on the packed daily agenda. The popular “quick lunchtime swim workout” referred more to the peripherals than the lap times – rushing out of the office, a presto change-o in the locke room, a one-minute post-workout shower, and then bursting back into the office an hour later with water beads still dripping from hair onto collar.

In contrast, the professional athletes – whose job was to simply race fast – lived lives centered around their workouts with minimal interference from real-life distractions or social obligations. While the pros conducted their workouts aggressively, the pace of their lives was leisurely Lunch time swim? Sure, but instead of toweling off, jerking the tie back into place and rushing out to the parking lot, the post-swim routine the pros consisted of lingering in the poolside spa for nearly as long as the workout, shooting the breeze, stretching tight muscles, and generally decompressing from the intense effort in the water. Eventually, the pack moved from the spa into an easy lunch involving more shooting of the breeze. Eventually, they remounted their bikes for a couple more hours of pedaling, then took an afternoon nap, followed by a late-day run, followed by a stretching/icing session, followed by a quiet evening of television, reading or lingering over a huge meal. As I spent more time in their world, I learned that the competitive advantage enjoyed by these professionals went beyond their impressive workouts. Embracing life both with purpose and at a more leisurely pace produces extraordinary results…”

In my own experience as a coach, I have personally witnessed this same scenario time and time again. The busy, CEO-type athlete who want to achieve it all and have success in work, in life and in sports tends to struggle under the consequences of constant stress far more significantly than the relatively less busy man or woman who has opted to work a normal 9-to-5 job and save the rest of their time for training – or even set aside their career temporarily to train.

The overachievers simply tend to get sick more, get injured more and have subpar results in their workouts, their racing and their events. This may not seem “fair”, but it's simply the reality of everybody having a finite biological stress coping mechanism.

The reason I want to share this with you is because you're probably an above average physically active person if you are reading this – and unless you're living in a pristine Himalayan resort on a mountaintop, you probably have to cope with significant amounts of lifestyle, relationship, emotional and work stress on a daily basis.

Once you dump your exercise stress on top of all those other stressors, you can easily overload your body's built-in physiological mechanisms to cope with X amount of stress. Heck, in America alone, simple, basic everyday stress without the added stress of exercise drives tens of millions of people to the point of illness, depression and self-destruction (15).

This is why suicide has surpassed car crashes as the leading cause of injury death, why a full third of employees suffer chronic debilitating stress, and why more than half of all “millennials” (18 to 33 year olds) experience a level of stress that keeps them awake at night with insomnia.

It's also a contributing factor to the growing number of people diagnosed with ADHD, anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder, and new research shows that stress renders you susceptible to serious illness – especially cancer and heart disease.

It's why controversial, mood-altering psychiatric drugs like SSRI antidepressants (complete with the FDA’s “suicidality” warning label) get popped like candy these days, along with Ritalin and similar psychostimulants. It's why nearly 30 percent of American adults have a drinking problem, and the reason why more than 22 million others using mood-altering drugs like marijuana, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens and inhalants – all in a desparate attempt to somehow cope with stress.

And by the way, don't sit too smugly if you don't live in America. One major study has concluded that nearly 40 percent of Europeans are plagued by stress-related mental illness – and substance abuse along with chronic disease are just as big an issue in other countries.

But wait – can't exercise reduce stress?

————————————————–

Can Exercise Reduce Stress?

It's true, to a certain extent, that exercise can help you cope with emotional stress.

In his excellent book Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain, author John Ratey (10) describes in great detail how exercise grows brain cells, improves functioning, allows for better focus, and significantly reduces stress. Here are a few highlights from the book:

-Exercising women lower their risk of dementia by 50%.

-Exercise can be as effective as antidepressants.

-Kids who exercised before school versus those who exercised in the middle of the day had better test scores.

-Exercise has been shown in multiple studies to reduce stress and anxiety.

One of the reasons exercise has such a powerful effect on stress is due to its effect on neurotransmitters, the signaling molecules that your body uses to talk to your brain, and vice versa. You have both “inhibitory” and “excitatory” neurotransmitters. The inhibitory neurotransmitters are serotonin and GABA, and these primarily make you feel happy and de-stressed, and can even help sleep when present in adequate amounts. However, if these hormones are depleted or low due to poor diet, lack of physical activity, or high stress, you can suffer from depression, insomnia, anger, and a vicious cycle of even more stress.

Meanwhile, you also have excitatory neurotransmitters, like glutamate, catecholamines, beta-phenylethylamine and dopamine. In balanced amounts, these excitatory neurotransmitters help to keep you alert, thinking sharply, focused and de-stressed. But in high amounts, they can cause more stress, panic, anxiety, and poor sleep.

The simple process of staying physically active can help keep these excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters balanced – which is a smart biological strategy to directly decrease or balance emotional and mental stress. A recent study from Penn State reported that people are more likely to have feelings of excitement and enthusiasm on days when they are more physically active, and a big part of this is that is this neurotransmitter balance (9).

But there's also a law of diminishing returns – and you need far less exercise than you think to lower stress or lower risk of chronic disease.

————————————————–

How Much Exercise Is Too Much?

How Much Exercise Is Too Much?

For example, one relatively recent study compared 3 groups of individuals over a 13 week period (7). The groups consisted of people who exercised 30 minutes per day, people who exercised 60 minutes per day, and people who didn’t exercise at all.

The subjects who were exercising were allowed to choose their activity, such as running, cycling, etc., but had to work fairly hard (about 70% maximum capacity) for at least 3 exercise sessions in their allotted exercise time. The rest of the time they could exercise as hard or as easy as they chose.

So what were the results?

Compared to the sedentary control group, both the 30-minute and 60-minute group lost 4% body weight and 14% body fat and 3% body weight and 13% body fat, respectively.

Metabolism actually increased slightly more in the 60-minute group than in the 30-minute group, but the maximum oxygen capacity of the 30-minute group slightly exceeded that of the 60-minute group. Interestingly, the people who exercised for 30 minutes tended to have a greater daily calorie deficit than the ones who worked out the entire hour, indicating less of a propensity to calorically compensate for their exercise sessions.

Ultimately, the group that exercised twice as much didn’t see anywhere near twice the benefit.

Another study tracked over 400,000 adults for 8 years, surveying them about physical activity levels and their health. Participants indicated what types of exercise they did and how many minutes per week they did each exercise, and then the researchers calculated a special number called a “hazard ratio” (HR) over the 8-year period of each person’s participation in the study (19).

A HR of 1 is assigned to a completely inactive group – reporting less than an hour a week of exercise and any HR lower than 1 means you have an increased chance of avoiding death.

Surprisingly, the researchers found that low-volume, moderate exercisers, who exercised just 75 minutes per week (that’s just 15 minutes a day), had significantly better HRs than inactive people, and this result held up even after controlling for a number of other factors, like age, sex, smoking, drinking, and other health issues. A change in HR like this means that for a typical 30-year-old, as little as 15 minutes of exercise a day leads to an increase of 2.5 to 3 years in life-expectancy. The study also showed that the health benefits of exercise significantly tapered off after anything more than 90 minutes of exercise per day.

So it turns out that you can exercise as little as 15 minutes a day to stay healthy, as little as 30 minutes a day to stay fit and lean, and that you don’t get any extra benefit once you exceed 90 minutes per day.

————————————————–

What Happens When You Exercise Too Much

In chapter 7, you learned about the adrenal glands and the four stages of adrenal exhaustion.

These stages were first identified back in the 1950's, when Dr. Hans Selye conducted some experiments creating stress in rats. Basically, the poor rats were forced to tread water with their legs tied until they became exhausted and died.

These stages were first identified back in the 1950's, when Dr. Hans Selye conducted some experiments creating stress in rats. Basically, the poor rats were forced to tread water with their legs tied until they became exhausted and died.

Dr. Selye then took the rats at various stages of tread-based drowning and dissected out their adrenal glands. He discovered that the adrenal glands responded to stress in several distinct stages. In the initial stage, the adrenal glands enlarge and the blood supply to them increases. But then, as the stress continues, the glands begin to shrink. Eventually, as the stress continues, the glands reach a completely depleted stage of adrenal exhaustion (20).

This all makes sense, because in a stressful situation, your adrenal glands are responsible for raising your blood pressure, transferring blood from your gut to your extremities, increasing your heart rate, suppressing your immune system and increasing your blood clotting ability. They work really damn hard to allow you to survive.

But this response is supposed to be short-lived – and not a constant “treading” day-after-day. For example, if one of our ancestors were walking through the forest and saw a wild animal, the adrenal glands would kick in. His or her heart rate would increase, their pupils would dilate, the blood would go out of their digestive system into the arms and legs, the blood clotting ability would improve, they would become more aware and their blood pressure would rise. At that point they'd either pick up a weapon and try to fight the animal or they would run.

And if they survived the ordeal, the chances are it would be a little while before a similar strain was put on the adrenal glands, and there would be opportunity to relax, eat, recover and play.

Our adrenal glands still work the same way, but most of us do not give our bodies the luxury of a recovery period for the overworked adrenal glands. As a result, we suffer from the ravages of chronic stress (23). The stimulation of the adrenal glands causes a decrease in the immune system function, so if you're under constant stress, you tend to catch colds and have other immune system imbalance problems, such as allergies or exercise-induced asthma. Blood flow to your digestive tract is decreased, so you get irritable bowel syndrome, constipation or diarrhea. The increase in blood clotting ability from prolonged stress can also lead to the formation of arterial plaque and heart disease. The list of deleterious response to stress goes on and on.

To effectively care for your adrenal glands, you must eliminate as much stress from your life as possible while at the same time maximizing your stress-fighting capabilities. While emotional stress is the type of stress most people think of when stress is mentioned, as you learned in Chapter 7, there are many other forms of stress you must manage and equip yourself against, including thermal stress from being exposed to extremes of temperature, chemical stress from pollution, rapid changes in blood sugar or pH and ingestion of food additives, molds or toxins, and of course, physical stress from heavy physical work, exercise, poor posture, spinal and structural misalignments, and lack of sleep.

As you've just learned, while science hasn't yet been able to tell us the exact number of minutes of exercise that it takes to shove your adrenal glands “over the edge”, we know that more than 90 minutes per day isn't doing us any extra favors from a health standpoint, and it's likely that the exact amount varies from person to person based on vitamin, nutrient and mineral status, training history, genetics, exposure to lifestyle, thermal, chemical and emotional stress, and even attitude.

————————————————–

The Mind-Body Connection

That's right: attitude.

For example, studies have shown that:

-Heart surgery patients with strong spiritual and social support have a mortality rate just 1/7th of those who do not.

-Meditation for just 30 minutes a day can be as effective as the use of antidepressants.

-Elderly people with positive attitudes have an over twenty percent reduction in risk of death from cardiovascular disease and over fifty percent lower risk from all other causes.

This is all based on something called the “mind-body” connection, and it's why the stress-fighting weapons you're about to discover in this chapter actually work. Science has clearly demonstrated that a healthy mind-body connection and the ability to have a positive mental attitude greatly affects your physical health and your adrenal response. (14)

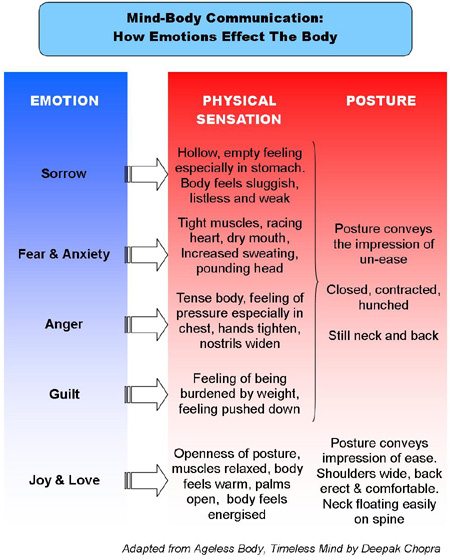

A healthy mind-body connection means that you can learn to use your thoughts and feelings to positively influence your body’s physical response. For example, if right now you were to stop reading and recall a time when you were happy, grateful or calm, your body and mind will automatically tend to relax. Go ahead, try it. Just think back to a wedding, a birth, a kiss, a snuggle, a hug, throwing up your arms as you cross the finish line of a race or any other awesome event in your life, and you'll feel your body respond.

Similarly, if you recall an upsetting or frightening experience, you may feel your heart beating faster, you may begin to sweat, and your hands may become cold and clammy. You can try this too. Close your eyes and imagine a time in your life when you were frightened, stressed, scared, under pressure or overwhelmed.

Feel that?

Your body responds.

Your heart rate picks up a little, your breath shortens, your hands slightly clench.

As you can imagine just by performing these simple thought exercises, if there are emotional, chemical, relationship and other stressors constantly present in your mind or body, there can be a real pile-up on your natural biological stress response, and all of these stressors acting together can act as a serious deterrent to adrenal recovery. If your adrenals aren't recovering, this severely limits the volume and intensity of physical activity your body can handle before it gets pushed over the edge.

But on the flipside, if you have extremely low levels of daily stress (something most of us don't have the luxury of experiencing unless we quit our job and move to a mountaintop), and/or you're mentally and emotionally capable of handling a wide variety of stressors, you're going to find yourself far superior in your capability to handle the stress curveballs that life throws your way. You may even find that you can actually handle a “busy CEO lifestyle” and still have huge success in sport, in health and in life.

But before we jumping into the weapons you'll need to handle all those stressors and make that success a reality, I'll repeat what I said way back in Chapter 3:

“…stress is stress – no matter whether it’s from exercise or from lifestyle, and the more stress you’re placing on yourself from your lifestyle, the less stress you’ll be able to place on yourself from exercise.”

So in this chapter, I'm going to give you seven of the best tools I've discovered for making your mind-body connection as bulletproof as possible, and ensuring that your body is equipped to handle as much stress as possible from lifestyle and exercise.

————————————————–

The Confusing World of Stress Solutions

Let's face it. Armed with captain Google, you can literally find millions of stress fighting articles, websites and books. And I'm not going to pretend that I can, in a single chapter of this book, comprehensively address every single stress-fighting method out there.

After all, just check out the Wikipedia entry for “stress management techniques“. You'll find:

- Autogenic training

- Social activity

- Cognitive therapy

- Conflict resolution

- Exercise

- Getting a hobby

- Meditation

- Mindfulness (psychology)

- Deep breathing

- Yoga Nidra

- Nootropics

- Reading novels

- Prayer

- Relaxation techniques

- Artistic expression

- Fractional relaxation

- Progressive relaxation

- Spas

- Somatics training

- Spending time in nature

- Stress balls

- Natural medicine

- Clinically validated alternative treatments

- Time management

- Planning and decision making

- Listening to certain types of relaxing music

- Spending quality time with pets

So yes – to control stress you could certainly grab a paint brush, adopt a kitten, and pipe some soothing sounds of nature CD's into your living room.

But if I were you, I would instead go after the big wins. The stuff that I've found over and over again to actually work for hard charging, physically active, stressed people like you and me control stress as quickly and effectively as possible.

And that's what we're going to go after in this chapter: the 7 best stress-fighting weapons I've found.

Ready? Here we go…

————————————————–

1. Breathing

Believe it or not, something you're doing right now (probably without even thinking about it) is a proven stress reliever: breathing.

And it turns out that deep breathing is not only relaxing, but it's been scientifically proven to positively affect your heart, brain, digestion, immune system – and possibly even your genes (13, 4). In the book Relaxation Revolution: The Science and Genetics of Mind Body Healing, author Herbert (Benson) discusses how breathing can literally change the expression of genes, and that by using your breath, you can alter the basic activity of your cells with your brain.

This isn't really new information. In India, breathing is called pranayama (which literally means “control of the life force”) and yoga practitioners have been using pranayama as a tool for influencing the mind-body connection for thousands of years. This is because breathing can have an immediate effect on your physiology by altering the pH of your blood and by changing your blood pressure.

Even more importantly, breathing can be used as a method to train your body's reaction to stressful situations and to dampen the production of stress hormones. This makes sense, since rapid, shallow breathing is controlled by your fight-and-flight sympathetic nervous system, but slow, deep breathing stimulates the opposing parasympathetic reaction.

So how do you know if you're breathing the wrong way? Here are seven warning signs:

1. You inhale with your chest. When you begin inhaling (breathing in), you may notice that your chest is the first thing to move, typically going up or slightly forward. If so, this is a sign that you are engaging in shallow or upper chest breathing.

2. Your rib cage doesn’t expand to the side. If you place your hands on either side of your rib cage when you breathe, you should notice that your hands move to the side about 1.5-2 inches as your trunk widens. If not, this is also a sign of shallow breathing.

3. You’re breathing with your mouth. Do you find that even when you’re not exercising, you commonly have your mouth open as you breathe? Unless you have a sinus infection or congestion that keeps you from breathing through your nose, your mouth should be closed as you breathe from deep within your nasal cavity.

4. Your upper neck, chest, and shoulder muscles are tight. Do you carry lots of tension in the muscles around and under your neck? If you get a massage, or you reach back and feel those muscles, do they feel painful, tender, or tight? If so, this can be a sign that you are engaging in stressed and shallow breathing.

5. You sigh or yawn frequently. Do you find that every few minutes, you must take a deep breath, sigh, or yawn? This is a sign that your body isn’t getting enough oxygen in your normal breathing pattern.

6. You have a high resting breath rate. A normal, relaxed, resting breath rate should be approximately 10-12 breaths per minute. If you measure how many times you’re breathing each minute and you exceed 12, this is a sign of quick and shallow breathing.

7. You slouch forward. Poor diaphragmatic control can cause specific muscles to become short and tight. Typically these muscles are your chest and the front of your shoulders. So if you find yourself slouching your head or shoulders forward, this can be a sign that you’re not activating your diaphragm when you breathe.

If you find that you experience any of the above seven signs that you’re not breathing the right way, there are lots of things you do about it. Here are 6 ways to train yourself to breathe properly:

If you find that you experience any of the above seven signs that you’re not breathing the right way, there are lots of things you do about it. Here are 6 ways to train yourself to breathe properly:

1. Blow up balloons. When you practice blowing up a balloon, it encourages you to contract your diaphragm and core muscles. You can enhance this effect by getting into a crunch or sit-up position on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the ground, then blowing up a balloon by inhaling through your nose and exhaling through your mouth. At the same time, try to maintain pressure against the ground with your low back.

2. Purse your lips. Practice breathing through pursed lips by creating as small a hole as possible in your mouth to breathe through. As you do pursed lipped breathing, this helps to keep you from breathing too fast. Take 2-4 seconds to breathe in through your nose, then take 4-8 seconds to breathe our very slowly through pursed lips, and practice this 1-2 times per day for about 3-5 minutes. Imagine you’re blowing through a straw, or trying to blow at a candle just hard enough for the candle to flicker, but not get extinguished.

3. Do planking exercises while deep breathing.Planking exercises like the front plank and side plank are fantastic for strengthening your core, can also be used to teach you how to breathe properly. Simply get into a front or side plank position and take 8-12 deep breathes from your bellybutton. Try to breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth.

4. Contract your abs as you breathe. A simple activity that can teach you how to use your abdominal (core) muscles to breathe better is to wrap your hand around your waist line, and then try to push your hands slightly away and out to the side as you breathe out. You should feel that your abdominal muscles are moving your hands as you breathe.

5. Upper chest resistance. Lie on your back, place a hand on your upper chest, apply slight downward pressure to the hard bone in the middle of your chest (your sternum) and try to maintain that pressure while you inhale and exhale. This will force you to “bypass” your chest while breathing, and instead breathe from deep within your belly.

6. Limit shoulder movement. Begin by sitting in a chair with your arms and elbows supported by the arms of the chair. As you inhale through your nose, push down onto the arms of the chair, and as you exhale through pursed lips, release that pressure on the arms of the chair. The purpose of this exercise is to keep you from elevating your shoulders while breathing (which can cause upper chest breathing).

Once you've learned proper breathing technique, things begin to get really interesting, because you'll have a newfound power that not only vastly improves your training efficiency and focus, but also controls how much cortisol your body releases during a workout by “putting the brakes” on your sympathetic nervous system while you're exercising.

As a matter of fact, when combined with the five-step formula I'm about to teach you, proper deep breathing is probably one of the most useful and effective relaxation and stress-control tools that I've ever discovered, and I first talked about it in detail in a podcast interview with John Douillard, the author of Body, Mind, and Sport: The Mind-Body Guide to Lifelong Health, Fitness, and Your Personal Best.

As a matter of fact, when combined with the five-step formula I'm about to teach you, proper deep breathing is probably one of the most useful and effective relaxation and stress-control tools that I've ever discovered, and I first talked about it in detail in a podcast interview with John Douillard, the author of Body, Mind, and Sport: The Mind-Body Guide to Lifelong Health, Fitness, and Your Personal Best.

In the podcast, titled “How To Breathe The Right Way When You're Working Out“, John explains how the simple act of nasal breathing (rather than mouth breathing) actually keeps your body in relaxation mode while you're exercising, and allows for an intense feeling of relaxation very similar to what you experience when you've finished a yoga or meditation session. You literally produce fewer stress hormones during a workout when you breathe the right way!

Since that initial podcast with John, I've combined the concepts he teaches in his book and during that interview with the rhythmic breathing strategies outlined in Budd Coates' book Runner’s World Running on Air: The Revolutionary Way to Run Better by Breathing Smarter. (8)

While I definitely recommend that you read Budd and John's books for the nitty-gritty details, here is the five-step formula I've designed to lower stress during even the most extreme exercise sessions and races.

——————————————

The Five Step Formula To Turn Extreme Exercise Into Relaxing Release

Think about the last time you took a series of deep, relaxing breaths. Orperhaps the last time you practiced yoga, took a refreshing nature walk, or simply stopped your hectic workday for a brief moment of reflection. How did you feel afterwards? Restored? Relaxed? Refreshed?

Think about the last time you took a series of deep, relaxing breaths. Orperhaps the last time you practiced yoga, took a refreshing nature walk, or simply stopped your hectic workday for a brief moment of reflection. How did you feel afterwards? Restored? Relaxed? Refreshed?

Next, contrast that sensation with how you felt during your last workout. Perhaps your mouth was gaping wide open as your panted from your chest while charging down a trail or pounding the pavement. Or maybe you were grunting and groaning forcefully as you struggled against a weight machine or barbell, or grimacing unpleasantly through a cardio, kickboxing or spinning session.

But what if you could create that same relaxing sensation of release that you feel in the first set of restorative activities when you’re performing that second set of stressful activities? What if exercise – even extreme exercise – did not send a catabolic hormone-packed message to your body that you are running from a lion or fighting in a battle, but instead provided you with relaxing release that left you feeling completely restored afterwards?

This completely defies the paradigm of the way most of us perceive we should feel during or after a tough workout, but with a simple series of steps you can actually transform extreme exercise into a relaxing release. You’re about to discover exactly how to make that transformation, with the following five-step formula.

1) Begin With Yoga

You must prepare your body correctly for extreme exercise, such as a hard bike ride, weight training session, run or competitive event. Sure, we’ve all heard that you must limber-up, warm-up, or perform dynamic stretches, but none of those activities prime your body for focused relaxation, or allow for an actual reduction in cortisol or activation of deep, diaphragmatic breathing patterns (3).

So you must precede extreme exercise with a brief series of basic salutations. It doesn’t take much – just 5 minutes will suffice. If you don’t know how to do basic sun salutations, simply watch this Howcast. You must especially focus on deep nasal breathing from your belly during this session.

Your body is now primed for relaxation during your workout.

2) Continue Deep Nasal Breathing

Hopefully you were already practicing deep nasal breathing from your belly while you were doing the pre-exercise yoga.

If you’re like most people who have gotten used to going into “fight-and-flight” mode during extreme exercise, the natural reaction for you as soon as you start your workout is to begin oxygenating through your mouth while engaged in shallow chest breathing.

Resist that temptation.

Instead, continue the deep nasal breathing from the belly, which will naturally relax your body and limit high amounts of stress perception and cortisol release. If you simply can’t get enough oxygen, slow down until you get to the point where you can do your nasal breathing, then gradually speed up again to your harder intensity. As you back off and re-approach the higher intensities, you get better and better at the deep nasal breathing. The more you practice this technique, the more natural it will become.

If you really struggle with nasal ventilation, and find yourself annoyingly congested, or continually short-of-breath no matter what you do, then try using a Breathe Right strips on your nose.

3) Rhythmic Breathing

Whether you’re lifting weights, running, or cycling rhythmic breathing is just as important as nasal breathing for keeping your body in a relaxed state no matter how hard you’re exercising.

Learning to rhythmic breathe is initially difficult, but become second nature within just a few days of practice. In a nutshell, when you’re running or cycling, you’re trying to inhale more than you exhale, and when you’re lifting weights your inhalation and exhalation are equal. And you are never, ever letting your breath become out of control or non-rhythmic.

If you’re running or cycling, simply take one deep nasal breath in for three foot strikes or pedal strokes, and one relaxed nasal breath out on the subsequent two foot strikes or pedal strokes. As you increase intensity and go faster, you can continue this breath pattern but speed things up by taking one deep breath in for two foot strikes or pedal strokes and one deep breath out on the subsequent one foot strike or pedal stroke.

If you’re lifting weights, release one deep nasal breath as you exert yourself and push or pull the weight, then one deep nasal breath in as you return the weight to it’s starting position.

Those are the basics of rhythmic breathing, and when combined with nasal breathing, this pattern allows for an intense feeling of relaxation and oxygenation after you finishing your workout, no matter how hard or heavy it is. If you need more direction, you’ll find additional helpful breathing resources at the end of this article.

4) Unplug

If you work around computers, phones, wi-fi routers, or any other “connected” scenario, you’ve no doubt experienced the brain fog, eye strain, muscle tightness and internal stress that can be created by constant exposure to electromagnetic fields (EMF). The effect of EMF on your nerves, cells, heart and brain is proven and substantial – which you'll learn about later in this book.

But your body remains exposed to that same electrical stress when you remain plugged in during your workouts, whether that be by carrying your smartphone during a secluded nature trail run or venturing into a gym jam-packed with TV’s and personal entertainment systems.

While there are some practical limitations to unplugging (e.g. you need to carry your phone for emergencies, or your only weight training equipment is at a fancy health club with lots of electricity), you should try to go out of the way to ensure your toughest workout sessions occur in as unplugged a state as possible.

No matter how much yoga you perform before an extreme exercise session, or how much nasal and rhythmic breathing you perform during that session, you simply won’t get the full removal of stress or the complete avoidance of a fight-and-flight reaction unless you remove yourself from electrical pollution during your workout.

5) Finish With Dedication

This last step sounds airy-fairy and inconsequential, but it's crucial.Avoid finishing extreme exercise by jumping straight into the shower, flopping onto the couch, or checking e-mails on your computer. Instead, just as you would with yoga or a meditation session, finish with dedication and relaxation.

To do this correctly, you should gradually slow down towards the end of the workout while continuing your focus on breath. Then, when your breath is completely controlled and your heart is no longer pounding, simply stop.

After you’ve stopped, close your eyes and dedicate the workout. You can dedicate it to yourself, to a loved one, to a teammate or workout buddy, or to whatever feels most important to you at the moment. Visualize that object of dedication in front of you, and acknowledge it respectfully. Take several deep nasal breaths in, fill your lungs, oxygenate your body, and finish with a full release of breath as you remove stress from your entire muscular and cardiovascular system.

Summary

You now have a complete knowledge of how to turn extreme exercise into relaxing release. When I first began practicing each of these concepts in my swim, bike, run and lift sessions, they felt foreign and counterintuitive. But my body adapted within just a couple weeks, and you’ll be amazed at the feeling of pure relaxation you can achieve even when you’re pushing your biology to the absolute limits.

As I mentioned earlier, if you want to learn more about deep nasal breathing, I’d recommend you read “Body, Mind, and Sport” by John Doullard, and to learn more about rhythmic breathing techniques, check out “Running on Air” by Budd Coates.

I realize that I've spent a lot of time simply talking about breathing.

The other stress-fighting weapons I teach you in this chapter will go by a bit more quickly, but here's the cool part: breathing forms the foundation of most of them, so you're equipped to sail through the rest of these concepts with ease.

And remember to practice your deep, nasal breathing as you keep reading.

——————————————–

2. Mindfulness Meditation

If there's one thing you probably wouldn't associate with the stereotypical soldier in the military, it would be sitting in a peaceful, zen-like position while practicing deep, relaxing meditation. But the military has actually found the practice of “mindfulness” to be extremely helpful in overcoming stress. (24)

And from Kobe Bryant to Joe Namath to Arthur Ashe, meditation has helped countless athletes (22) manage stress, improve focus and enhance performance.

The very best place to begin learning meditation is the simple act of mindfulness, which is how I learned to meditate, and is how I now start every single day. I actually practice mindfulness before I even get out of bed in the morning, and usually pair it with heart rate variability readings from my Sweetbeat tracker so that I can assess how mindfulness practice is directly influencing my stress levels. The results are pretty astounding. I can literally raise my HRV number by 5-10 points with just a few minutes of morning mindfulness practice.

Mindfulness is a type of meditation that involves focusing your mind on the present. To be mindful is to be aware of your thoughts and actions in the present, without judging yourself, and without being distracted by stressful experiences from the past (e.g. how crappy the day before was) or stressful anticipation of the future (e.g. everything you need to get done that day).

Research has proven that mindfulness meditation can improve mood, decrease stress, and even boost immune function (16).

Here's how to start:

1. Find a quiet and comfortable place. I recommend you sit in a chair or directly on the floor with your head, neck and back straight but not stiff.

2. Try to put aside all thoughts of the past and the future and stay “in the present”.

3. Become aware of your breathing, focusing on the sensation of air moving in and out of your body as you breathe using the techniques you've already learned in the chapter. Feel your belly rise and fall, the air enter your nostrils and leave your mouth through pursed lips, or leave your nostrils.

4. Watch every thought come and go, whether it be a worry, fear, anxiety or hope. When thoughts come up in your mind, don't ignore or suppress them but simply note them, remain calm and use your breathing as an anchor.

5. If you find yourself getting carried away in your thoughts, observe where your mind went to (without judging yourself) and simply return to your breathing. Remember not to be hard on yourself if you become distracted.

6. As the time comes to a close, sit for a minute or two, becoming aware of where you are. Then get up gradually.

Once you learn mindfulness based meditation, you can easily start or end each day with it – a practice I highly recommend. One of my favorite free audio resources that will actually walk you through a mindfulness session, or a different type of meditation called “progressive relaxation”, can be found at: http://www.buddhanet.net/audio-meditation.htm.

Toss these track into your .mp3 player and try them out. I especially like the “body scan“. I used to think mindfulness meditation was for strange hippies, but now it's the first thing I do every day, and it makes a huge difference in stress levels throughout the day.

———————————————

3. Yoga

3. Yoga

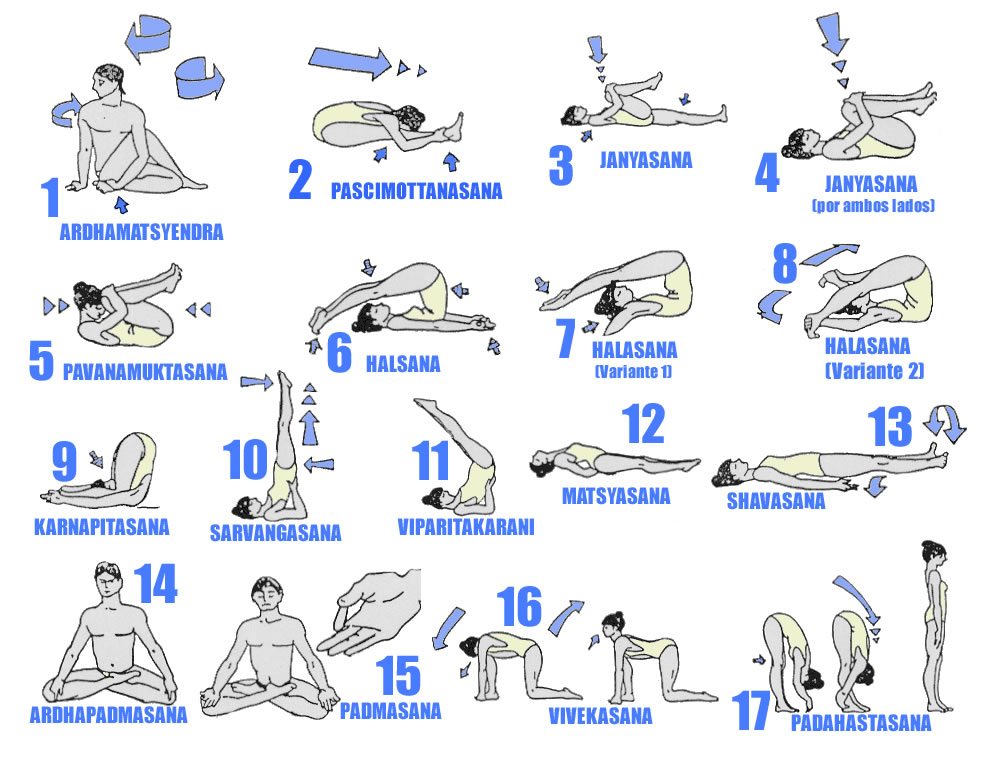

You probably don't need me to tell you that yoga is good for stress. Sure – you've already learned that yoga is not the best idea prior to any activity for which you need speed, strength or power, and it's also not the best way to improve flexibility, but when it comes to stress, yoga is definitely one of my top seven stress-fighting weapons (11), and I personally follow up my morning mindfulness meditation with a good 5-15 minutes of yoga (in addition to beginning and/or ending workouts with the sun salutations you already learned about).

Yoga has a ton of different styles, forms and intensities, but hatha yoga, in particular, is a good choice for stress management – particularly if you've perfected the breathing style you learned earlier in this chapter. Hatha is one of the most common styles of yoga, and most beginners appreciate its slower pace and easier movements.

In contrast, some yoga is actually quite stressful. Take Bikram Yoga (AKA “Hot Yoga) for example. Bikram actually a hybrid form of Hatha Yoga that you do in a hot room, and Bikram is really useful and effective when you're acclimating for a hot race or trying to build up your body to handle the heat, and I personally try to throw in 4-8 weeks of weekly Bikram leading into Ironman Hawaii. Because you get so hot and sweaty, Bikram can also be good for detoxing and for strengthening the cardiovascular system when you're trying to avoid joint impact from something like running.

But Bikram is also stresssful. As you body shunts blood to your extremities in a rapid attempt to cool, your heart rate goes through the roof, and because of this, Bikram would definitely considered to be one of the “thermal stressors” I referenced it earlier.

Or take, for example, some of the more extreme forms of power yoga that you'll find in gyms and DVD's. I own one such program called “Yoga for The Warrior“, which is a home DVD that features TV's Biggest Loser personal trainer Bob Harper. From start-to-finish, the thing features rollicking rock music, teeth-gritting holds, and the screaming voice of Bob telling me to make it even harder.

Sure, that's a good workout, but it's not stress controlling or lowering. So choose your yoga wisely.

Hatha yoga promotes physical relaxation by decreasing activity of the sympathetic nervous system, which decreases cortisol, lowers heart rate and increases breath volume, so that's my personal recommendation. It's easy to learn and you can see some of the basic moves below. Once you've memorized some of the basic moves, you can easily take Hatha Yoga outside of a classroom or DVD setting and just throw together your own stress-relieving routine on the spot, which is what I usually do – since I rarely have the time to actually schedule and attend a class.

———————————————

4. Tai Chi

4. Tai Chi

Tai chi is a system of slow, graceful exercises that combine movement, meditation and rhythmic breathing to improve the flow of chi (AKA your life force). Research has shown that that Tai Chi can reduce stress, lower blood pressure and help improve posture, balance, muscle tone, flexibility and strength (2).

Tai Chi is typically taught in groups in health centers, community centers, offices and schools, but Amazon has a variety of good DVD's and books for learning Tai Chi, and I personally own and use the one pictured left “Tai Chi for Beginners“.

I'm not sure if it's because Tai Chi is so slow and precise or because it makes me feel like some kind of ancient Chinese monk while I'm performing the various body movements and positions, but my stress levels hit rock bottom after finishing a Tai Chi session. I do a Tai Chi session at least once a month, and during easier recovery weeks, will do one to two sessions in a week.

Because of it's stress-reducing efficacy, a weekly Tai Chi session is an integral and “non-optional” part of the programs that I personally oversee for individuals who are recovering from overtraining or adrenal fatigue.

If you're not dealing with adrenal issues, then I think you may find bigger bang for your time buck with a yoga and meditation – but because of the distinct correlation between chi, cortisol and your adrenals, and the variety of practitioners (including hardcore Paleo powerlifter Robb Wolf) who recommend Tai Chi for fixing overtraining adrenal fatigue, I'm a personal fan of learning this ancient art.

———————————————

5. Coherence

Get ready to take a deep dive into hardcore heart and brain science for a quick moment. I promise it won't hurt too much.

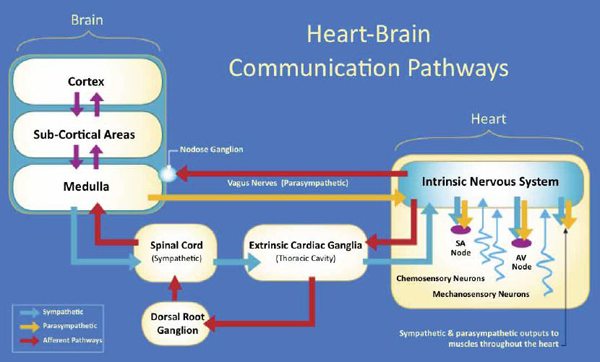

Your heart is in a constant two-way dialogue with your brain – a “heart-brain connection”. Interestingly, your heart (and entire cardiovascular system) are sending far more signals to your brain than your brain is sending to your heart (17).

These “afferent signals”, or signals that flow to the brain, have a regulatory influence on many aspects of your nervous system, including most of your glands and organs. And these signals also have profound effects on your higher brain centers. Cardiovascular afferent signals have numerous connections to important brain centers as your thalamus, hypothalamus, and amygdala, and because of this, the signals from your heart play a direct role in determining your perceptions, thought processes, emotional experiences and overall stress.

The research field of “neurocardiology” has firmly established that your heart is indeed a sensory organ and an information encoding and processing center, and almost like a second brain. The heart's circuitry allows it to learn, remember, and make functional decisions independent of your cranial brain, which is mind-blowing to think about. But the fact that the heart has an intrinsic nervous system and is itself a complex, self-organized system capable of forming new neural connections has been well demonstrated.

The diagram below illustrates this heart-brain connection, and show the direct connection from your heart's neurons to organs such as your lungs, esophagus, skin and arteries.

As you can probably imagine, this connection between your heart and brain is a topic that could fill an entire book alone. Organizations such as the Heart-Math institute have enormous depths of free research and articles on the topic, but the basic idea is that your heart is a primary generator of rhythm in your body, and the heart can directly influence brain processes that control your nervous system, cognitive function and emotion.

So when your heart rhythms are in a state of “coherence”, this can facilitate smoother brain function, which not only decreases stress but also allows you more access to your innate intelligence – which allows you to improve your focus, creativity, intuition and higher-level decision-making. If you've ever felt in “The Zone”, then you've experienced ideal heart-rhythm coherence. Similarly, if you test your heart rate variability and it is high, this is also a good sign that your are in a state of coherence. As a result, you tend to feel confident, positive, focused and calm yet energized.

Conveniently, you can create a coherent state in about one minute flat by using a strategy called “Quick Coherence”.

This is a fast and powerful technique you can use immediately when you begin feeling a stressful emotion such as frustration, irritation, anxiety or anger – and a technique that I'll even use prior to situations when I know I'm going to experience stress, such as an important business meeting, public speaking engagement, tennis match, or triathlon.

Here's how to achieve coherence and optimize communication between your heart and your brain, in three easy steps:

Step 1: Heart Focus. Focus your attention on the area around your heart, the area in the center of your chest. If you prefer, the first couple of times you try it, place your hand over the center of your chest to help keep your attention in the heart area.

Step 2: Heart Breathing. Breathe deeply, but normally, and imagine that your breath is coming in and going out through your heart area. Continue breathing with ease until you find a natural inner rhythm that feels good to you.

Step 3: Heart Feeling. As you maintain your heart focus and heart breathing, activate a positive feeling. Recall a positive feeling, a time when you felt good inside, and try to re-experience the feeling. One of the easiest ways to generate a positive, heart-based feeling is to remember a special place you’ve been to or the love you feel for a close friend or family member or treasured pet. This is the most important step.

Using Quick Coherence at the onset of stress can keep the stress from escalating into a physiological damaging or adrenal draining situation, and I've found this technique to be especially useful after an emotional “blowup” to get back into balance quickly.

The nice thing about the Quick Coherence technique is that you can do it anytime, anywhere and no one will know you’re doing it. But in less than a minute, it creates positive changes in your heart rhythms, which then sends powerful signals to the brain that directly affect your body via the mind-body connection.

You can visit the HeartMath institute to learn even more about coherence and the research behind it. For useful, live biofeedback and watching your heart rhythm and heart rate variability in real time as you practice coherence (which can be extremely helpful, especially when you're first learning coherence), you'll need either an emWave2 unit or the Inner Balance sensor for your smartphone .

———————————————

6. Learn

As we near the end of this section, I'm going to get all airy-fairy on you again.

Earlier, I made a joke about grabbing a paint brush or getting a kitten to reduce stress. But I was kind of not kidding.

Just think about it: how many hardcore triathletes, marathoners, cyclists and Crossfitters do you know who pretty much A) work; B) exercise and C) eat.

Every single day is the same routine, day-in and day-out. Eat a big breakfast, check off your WOD or workout, get through the workday, eat a big dinner, sleep and maybe throw in some TV or reading every now and again.

But from music (5) to art (18) to journaling (6), having some kind of a hobby (21) and engaging in regular learning has consistently been shown to lower stress. And let's face it: when you're on your deathbed do you really want to lie there thinking about how good of an exerciser you were?

That's why I personally play guitar. My rule is that three times a week, I practice my guitar for 20-30 minutes. That's it. And considering I played violin for 13 years with an hour of practice every day, an hour a week of guitar is not too difficult to find time for. Musical instruments as a hobby are also good because you get the added benefit of the proven stress relieving effects of music.

But that's not all.

Two times per week, I cook. And it can't be scrambled eggs or stir fry. It has to be a new recipe that stimulates my brain, creates new neural pathways, and helps to decrease stress. Last week it was vegan Pad Thai one day and fried liver another day (yes, I am an classic omnivore). You'd be surprised at how stress relieving cooking is, especially compared to eating, which can actually be stressful for many people, especially body-conscious athletes.

And at least once a month, I learn something else new. This can include attending a community dance class with my wife, learning a kick serve for my tennis game, growing a mint plant in the backyard, or dribbling a basketball between my legs. Teaching activates similar stress-relieving neural pathways as learning, and if you have children, this can be a big bonus. For example, this month, I'm teaching my twin boys how to play chess and speak Thai.

It doesn't really matter what you're teaching or learning, as long as you're pretty much doing anything that doesn't involve the daily routine of work, swimming, cycling, running, lifting or eating.

Need a good resource to get your creative wheels turning? Check out the Top 40 Useful Websites For Learning New Skills. Also, from cooking to music to cards, Tim Ferris's “4 Hour Chef” book is a fantastic resource for getting inspired to learn and also for picking up ideas about new things to learn.

———————————————

7. Sleep

Ah yes, sleep.

Right up there with breathing, sleep is one of the most important stress-fighting weapons on the face of the planet (25, 12).

Sleep is so important actually, that I am going to devote the entire next chapter to enhancing deep sleep and giving you the best sleep-hacking, insomnia, jet lag and napping tools.

In other words, you'll need to wait a few days for details and how-to's on the final stress-fighting weapon.

For now, just know this: not protecting and prioritizing sleep is one of the best ways to slowly kill yourself.

——————————————

Summary

In the meantime, remember that just because you're adding all these stress-fighting weapons to your arsenal, you can't necessarily use your newfound techniques as an excuse to simply pile more exercise or lifestyle stress on your body. No matter how many of these techniques you use, you still need to measure stress and exercise preparedness using the recovery-tracking strategies you learned in Chapter 7.

But as you implement breathing, meditation, tai chi, yoga, coherence, a hobby and sleep into your daily routine, you're going to find yourself far more capable of handling the stress that life is throwing at you, and more capable of recovering from the stress that you are throwing at your own body.

And as usual, leave your questions, comments and feedback about the best ways to stop stress below, as well as any glaring editorial mistakes I need to personally stress about!

——————————————

Links To Previous Chapters of “Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance, Health & Life”

Part 1 – Introduction

-Preface: Are Endurance Sports Unhealthy?

-Chapter 2: A Tale Of Two Triathletes – Can Endurance Exercise Make You Age Faster?

Part 2 – Training

-Chapter 3: Everything You Need To Know About How Heart Rate Zones Work

–Chapter 3: The Two Best Ways To Build Endurance As Fast As Possible (Without Destroying Your Body) – Part 1

–Chapter 3: The Two Best Ways To Build Endurance As Fast As Possible (Without Destroying Your Body) – Part 2

–Chapter 4: Underground Training Tactics For Enhancing Endurance – Part 1

–Chapter 4: Underground Training Tactics For Enhancing Endurance – Part 2

–Chapter 5: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 1: Strength

–Chapter 5: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 2: Power & Speed

–Chapter 5: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 3: Mobility

–Chapter 5: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 4: Balance

Part 3 – Recovery

–Chapter 6: How The Under-Recovery Monster Is Completely Eating Up Your Precious Training Time

–Chapter 7: 25 Ways To Know With Laser-Like Accuracy If Your Body Is Truly Recovered And Ready To Train

–Chapter 8: 26 Top Ways To Recover From Workouts and Injuries with Lightning Speed

-Chapter 9: 7 Of The Best Ways To Beat A Hidden Killer That Keeps Completely Sabotages Your Recovery.

——————————————-

References

1. Benson, H. (2011). Relaxation revolution: The science and genetics of mind body healing. (1st ed.). New York, NY: Scribner.

2. Biscontini, L. (2012, March 07). What exactly is tai chi and what are some of its benefits?. Retrieved from http://www.acefitness.org/blog/2430/what-exactly-is-tai-chi-and-what-are-some-of-its

3. Brown, R.P., Gerbarg, P.L. Yoga breathing, meditation, and longevity. Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2009 Aug; 1172:54-62

4. Cea Ugarte, J.I., Gonzalez-Ointo Arrillaga, A., Cabo Gonzalez, O.M. Efficacy of the controlled breathing therapy on stress: biological correlates (preliminary study). Universidad Pais Vasco, Escuela de Engermeria. Revista de Enfermeria, Barcelona, Spain. 2010 May; 22(5): 48-54.

5. Cervellin, G., Lippi, G. U.O. From music-beat to heart-beat: A journey in the complex interactions between music, brain, and heart. Pronto Soccoroso e Medicina d’Urgenza, Dipartimento di Emergenza-Urgenza, Azienda Ospedaliero, Universitaria di Parma, Italy. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 2011 Aug; 22(4): 371

6. Charles JP. Journaling: creating space for “I”. Clayton State University Morrow, Georgia, USA. Creat Nurs. 2010;16(4):180-4

7. Church TS, Martin CK, Thompson AM, Earnest CP, Mikus CR, et al. (2009) Changes in Weight, Waist Circumference and Compensatory Responses with Different Doses of Exercise among Sedentary, Overweight Postmenopausal Women. PLoS ONE 4(2): e4515

8. Coates, B. (2013). Runner's world running on air: The revolutionary way to run better by breathing smarter. New York, NY: Rodale Books.

9. Conroy, D. (2013). Physical activity yields feelings of excitement, enthusiasm. Retrieved from http://www.hhdev.psu.edu/news/2012/Physical-Activity-Feelings.html

10. John, R. (2013). Spark: The revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain. (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company.

11. Diezemann, A. Tagesklinik fur inderdisziplinare, Schmerztherapie, DRK Schmerz-Zentrum Mainz, Auf der Steig, Mainz, Relaxation techniques for chronic pain. Germany. Schmerz, 2011 Aug: 25(4): 445-53.

12. Faraut B, Boudjeltia KZ, Dyzma M, et al. Benefits of napping and an extended duration of recovery sleep on alertness and immune cells after acute sleep restriction. Brain Behav Immun. 2011 Jan;25(1):16-24. Epub 2010 Aug 8.

13. Kaushik, R.M., Kaushik, R., Mahajan, S.K., et al. Effects of mental relaxation and slow breathing in essential hypertension. Department of Medicine, Himalayan Institute of Medical Sciences, Swarmi Rama Nagar, Uttaranchal, India. Complemantary Therapies in Medicine. 2006 Jun; 14(2):120-6.

14. Makhija, N. (2012). Mind – body connection. Nurs J India., 103(4), 163-4.

15. Manocha, R., Black, D., Sarris, J., et al. A randomized, controlled trial of meditation for work stress, anxiety and depressed mood in full-time workers. Discipline of Psychiatry, Sydney Medical School, Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney University, St. Leonards, Australia. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011: 960583

16. Marchand, W.R. George E. Wahlen Mindfulness-based stress reduction, minduflness-based cognitive therapy, and Zen meditation for depression, anxiety, pain, and psychological distress VAMC and University of Utah, Salt Lake City, USA. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 2012 Jul;18(4):233-52

17. McCraty, R. (2009). The coherent heart heart–brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. In Integral Review (Vol. 5, p. 2). Boulder Creek, CA: HeartMate Reseach Center.

18. Mimica N, Kalinić D. Art therapy may be beneficial for reducing stress-related behaviors in people with dementia—case report. Psychiatr Danub. 2011 Mar;23(1):125-8.

19. Pang Wen, C. (2011). Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet, 378(9798), 1244-1253.

20. Selye, H. “Stress and disease”. Science, Oct. 7, 1955; 122: 625-631.

21. Sloan DM, Feinstein BA, Marx BP. The durability of beneficial health effects associated with expressive writing. National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare Systems. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2009 Oct;22(5):509-23.

22. The Huffington Post. (2013, July). Athletes who meditate: Kobe bryant & other sports stars who practice mindfulness. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/05/30/athletes-who-meditate-kobe-bryant_n_3347089.html

23. The stress of life. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1956.

24. Vujanovic, Niles, Pietrefesa, Potter, & Schmertz. (2010, September 20). Potential of mindfulness in treating trauma reactions. Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treatment/overview/mindful-PTSD.asp

25. Ward TM, Gay C, Alkon A, et al. Nocternal sleep and daytime nap behaviors in relation to salivary cortisol levels and temperament in preschool-age children attending child care. Biol Res Nurs. 2008 Jan;9 (3):244-53.

Nice Post!! Thanks for sharing

Is it possible for a teenager to have adrenal fatigue?

Yes. Being young-er doesn't make you immune to stress and over training.

Hey Ben, I notice that you reference Seyle. What do you think of the work of Danny Roddy or Matt Stone? They’re followers of Seyle and Ray Peat. A lot of what they say makes great sense, and lot of it is completely against everything I’ve learned- like eating lots of sugar, and taking aspirin etc. Do you have any thoughts on their philosophy?

I don't really follow Danny or Matt much Cathy, but I do like just about everything Ray Peat puts out…

Awsome chapter Ben! Coping with stress is definitely something a lot (including myself) need to improve on. Lookin forward to the sleep chapter ;) I find it particularly difficult to sleep during periods of stress. Which is the bummer…

Hi Ben,

You are a nice person. Not just because your share research and training methodologies to the world. But because of the work and heartfelt effort you put in these articles to express your knowledge to the wellness of others.. Every time I read your articles; I tend to draw parallels to every step of Maslow’s pyramid. You articles cover right from our physiological existence to self-actualization. Thank you for your constant effort in helping people realize their potential.

Our garden of human knowledge is only tended by constant gardeners like you,

With wishes to you and your family,

TJ

Hey thanks…that means a lot! Just wait for tomorrow's post TJ…you'll love it!

Great info!

I’ve got questions:

What is the definition of exercise? Is it 70% or more HR? If I go for a 2 to 4 hour long easy trail run and my keep my heart rate under 110, is that exercise? (Training for a 100 mile ultrarace) Is Doing yoga exercise? How about weight training? I’m just trying to see where my boundaries are. I can go for a 90 min run under 7 min pace and stay below 70% HR.

Thank Ben!

Anything that takes you up above about 60% of your max HR so far in research. But think about it this: anything that is over and above "hunting-gathering" heart rate…

Hi Ben, what can I say, I just had a quick read through your article and I love it.

I will read it again. And again.

You see, I’m kind of a living example for a lot you are mentioning here.

I train for triathlons.

I’m an extreme low-volume triathlete (partly because luckily I get a lot out of training sessons, and partly because I need the extra recovery time in between workouts).

I’ve also some mental issus (some chronical ones in addition to anxiety and depressive episodes) so I know what it is like when emotional stress and negative thoughts diminish my training benefits.

I do use training to reduce stress, but I also experience that training is stressing the body (in contrary to all those “happy-runners” out there, that gets TONS of energy from running EVERY DAY.

I mean I get exhausted from running. Yes, I like it and enjoy it, but in the end, it stresses my body so it has to recover.

I’m right now NOT working at all, due to my “disability to work”. Wouldn’t that be every triathlete’s dream, to have the whole day, almost every day, to train and rest?

But I experience the severe stress of mental issues, and this spring, I had to reduce my training volume much more compared to the 70% I had planned (I was lucky to get Dave Scott as a coach for my IM 70.3 in Norway, I won it as a prize, wow, that was fantastic, but boy what a training schedule!! I’m looking forward to race, because I can finally take a rest :D).

I always thought that since I’m physically really fit (have been since I was a kid, great genes!) I would be able to train like I was “healthy” but the effect of mental and emotional stress is much stronger than I thought (and I DO live in a little place in the mountains in peaceful Norway! But when my mind is freaking out – there is not much peace inside).

Mindfullness is something I find very beneficial. Especially since I have had breathing problems for several years when under a lot of stress, my diaphragm just stiffens. Learning to breathe deeply is really a good way to reduce stress.

Making time for mindfulness, if even only for 5-10min, helps me a lot, too.

I already have a dog, but I also started to be more creative (crocheting beanies and painting), which I think is a great way to balance the rather demanding “strong/aggressive” character of training (Dave Scott likes high intensity, don’t I just love the VO2-max intervals! :D).

Another experience is, that I DO get better after a workout (getting my brain chemicals in order) but more is not better.

I mean I have done a full Ironman in 2010, and that was really a great experience, but training for shorter distances is actually more beneficial for my health.

It’s almost as if my nervous system gets resistant to huge loads of training. I mean, there is certainly no linear correlation between training volume and serotonine production I guess!

Since I don’t work but have something like three professions and many years of education, I can also experience too little stress, so I started to learn – again – this is something I enjoy.

I study anatomy and physiology, that gives me something new to learn, and is even beneficial for my training since I understand it better theoretically.

So, this summer I will finally learn Yoga, because that is something I’m missing, I’ve always wanted to learn, and this summer, I will!

Sleep is something I try to do my best about, but nightmares I guess will be there as long as I’m having therapy, I guess it’s just the natural way of my brain to continue working with earlier issues…

But as for the nasal breathing you recommended, I tried that on my very slow runs, just for fun, but that was really hard.

My nostrils are really small. Even when I’m lying on my left side, I have to try to use the pillow or something to open them up a bit so enough air gets through the right one (too much information? I hope not…) – They are normal looking, but maybe my nostrils are too small inside???

But I guess some facial muscles are trainable to do the job (like you can see with horses that work hard).

Are you still with me?

Thanks for reading then, like I said, I love this article, and I’ll read it several times later.

Now I have to pack my triathlon stuff and get my bike in the bike bag so I can get to Haugesund tomorrow.

A whole week training with Dave Scott is waiting (so who am I to complain about my small nostrils???).

Keep up the good work and thanks for sharing those great articles!

Imke

Great comment, Imke! You would be surprised at how much you can get through your nostrils if you really learn how to nasally breathe the right way. I would get John Douillard's book for sure. Tell Dave Scott I said hi, and enjoy that week of training, man!

ben: This gets better and better as you articulate the ins and outs of your advice. This is essential reading and listening for me weekly. Thanks.