November 30, 2015

I'm infatuated with water.

Always have been.

But despite playing water polo in college, swimming in open water swim competitions in the Caribbean, competing in a decade of Ironman triathlons, taking daily cold water plunges, and even using the soothing sounds of water to help me sleep, I never really knew why I was so drawn to water until, last month, I read the book Blue Mind: The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, In, On, or Under Water Can Make You Happier, Healthier, More Connected, and Better at What You Do.

In Blue Mind, author Wallace J. Nichols combines cutting-edge neuroscience with compelling personal stories from top athletes, leading scientists, military veterans, and gifted artists to show how proximity to water can improve performance, increase calm, diminish anxiety, and increase professional success – and why some people, like me, are genetically hardwired to have a strong, magnetic draw to water.

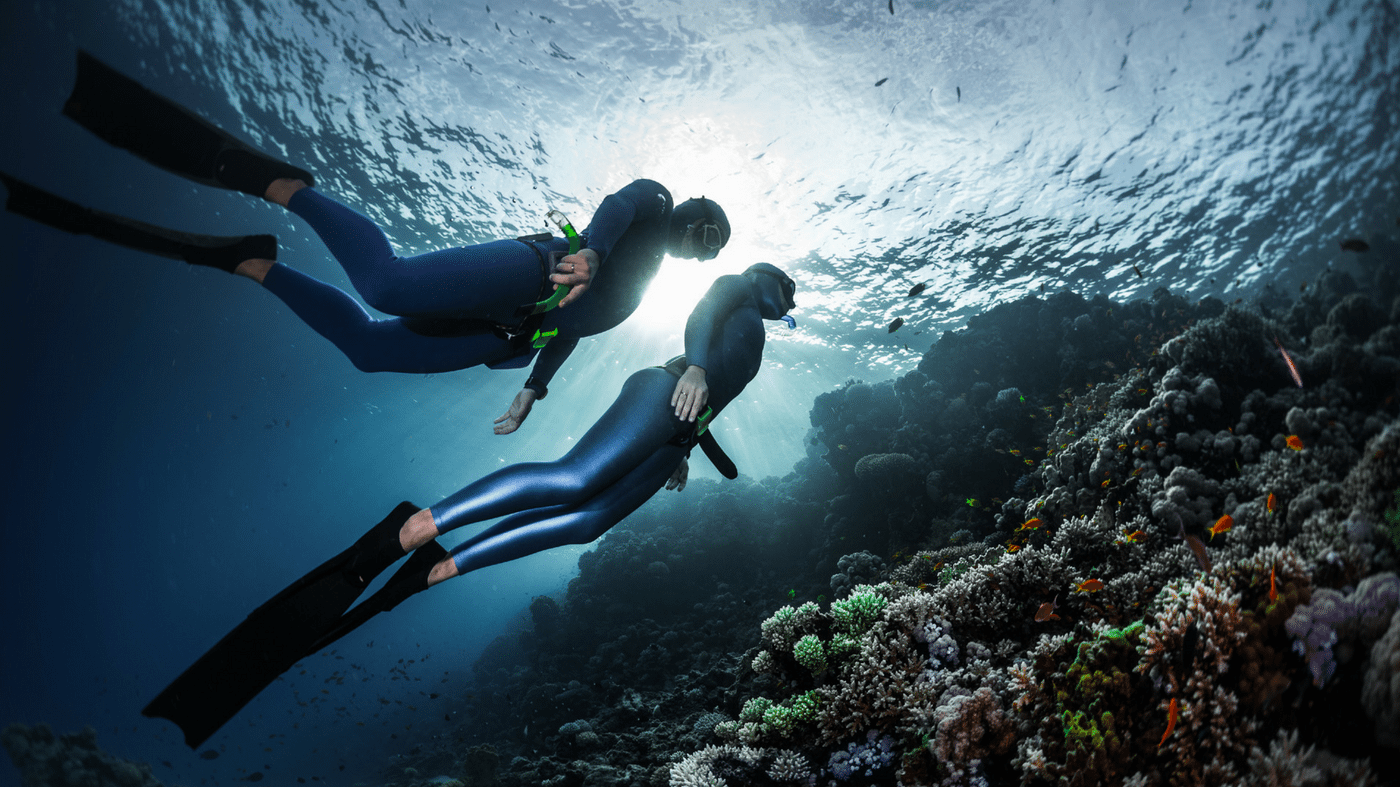

Perhaps this relationship with water is why one another favorite book of mine is also about the intimate and intense interaction of the human body and brain with water. That book is Deep: Freediving, Renegade Science, and What the Ocean Tells Us about Ourselves, and last year, I released an intriguing podcast episode with James Nestor, the author of Deep.

During that podcast, entitled “The Extreme Sport You’ve Probably Never Heard Of, And How You Can Use It’s Renegade Techniques To Become Superhuman“, James highly recommended that I tap into the sport of freediving to become a stronger man, to become a better athlete, and to satisfy my primal urge to be in or near water. James even recommended a specific location that I should visit to learn exactly how to do this, a place in Fort Lauderdale, Florida called “Immersion Freediving“.

You're about to learn how that simple suggestion from James morphed into an incredible adventure that includes breath-holding, blood-doping, shark-chasing, ketosis, spearfishing and a reactivation of one of the most primal reflexes known to man.

————————

Now, allow me to clarify something: I don't want to be a competitive freediver.

Competitive freediving looks like this:

Impressive? Yes.

Something I have a deep desire to do? No.

So, considering I have close to zero interest in traveling in a straight vertical line up and down in the ocean to touch a mysterious metal plate plunged at hundreds of depths of feet, why do I really want to learn to freedive?

Three reasons, really, and here they are:

1) Staying Calm In The Face Of Extreme Stress

As the Wall Streets Journal reports in the article “Why Olympic Athletes Are Learning To Hold Their Breath For More Than Five Minutes“, the goal of some of the world's best athletes who have turned to freediving to enhance their performance is to learn how to control breathing and stay relaxed under uncomfortable, extreme circumstances, then adapt those lessons to moments of panic in more familiar surroundings – like staring down an icy mountain slope and facing a series of death-defying airborne flips and twists.

A big, big part of freediving involves learning how to consciously and nearly instantly lower your heart rate, how to maintain control of your body and tolerate the discomfort when your diaphragm begins producing incredibly painful and disturbing contractions, and figuring out how to be a complete ninja when it comes to some of the world's top relaxation breathwork techniques, like box breathing, 2-2-10-2 breathing, pranayama breathing, purging, packing and a host of other respiratory weapons.

In other words, freediving teaches you how to rewire and take near complete control over your primal fight-or-flight instinct. I would very much dig having that skill.

Yep, freediving skills make you zen.

2) Activating The MDR

The Mammalian Dive Reflex, or MDR, is a deeply ancestral reflex in which your body changes its entire physiology to allow it to stay underwater for extended periods of time. It is exhibited strongly in aquatic, diving, underwater mammals like seals, otters, and dolphins, but it also exists in other mammals, including humans.

We all have the MDR when we're babies. Then, at about 6 months old, when it no longer serves us to suck in an enormous breath of air after popping out of our mom's uterus, we lose the reflex.

So why do I want my MDR back?

Upon initiation of the reflex, several changes happen to a body, in this order:

Bradycardia, a lowering of the heart rate, is the first response to submersion. Immediately upon facial contact with cold water, the human heart rate slows down ten to twenty-five percent. This means if your resting heart rate is, say, 50 beats per minute, it can slow to under 20 beats per minute. Elite freedivers have shown a heart as low as 8 beats per minute when diving deep. Seals experience changes that are even more dramatic, going from about 125 beats per minute to as low as 10 on an extended dive. Slowing the heart rate reduces the need for oxygen in the bloodstream, which leaves more precious oxygen to be used by your other organs.

After the heart rate drops, peripheral vasoconstriction, which is a narrowing of vessels in your extremities, sets in. When under the high pressure induced by deep diving, the capillaries in your extremities start closing off, which stops blood circulation to those areas. Toes and fingers close off first, then hands and feet, and finally arms and legs stop allowing blood circulation, leaving more blood for use by your heart and brain. But your muscles can have as much as 12% of their oxygen storage in muscle, and so they can keep working long after capillary blood supply is stopped. Your body begins to become a highly efficient oxygen-utilizing machine.

Then the blood shift occurs. Peripheral vasoconstriction in the extremities starts as soon as you get in the water, pushing blood into your thoracic organs in your chest cavity, particularly your lungs. This engorges the alveolar capillaries in your lungs, increasing gas pressure and the pressure inside the chest. As depth increases, peripheral vasoconstriction and hydrostatic pressure on the extremities continue to drive the blood shift. When depth increases to the point where chest compression limits are reached, the blood shift accelerates. The blood shift keeps pressure inside the chest high enough to allow a diver to proceed deeper without the chest collapsing.

Your brain temperature is actually dropping this whole time. This is why both a conscious and an unconscious person can survive longer without oxygen under water than in a comparable situation on dry land,.The exact mechanism for this effect is likely a result of brain cooling, similar to the protective effects seen in patients treated with deep hypothermia. When your face is submerged in water, even it's not extremely cold, receptors that are sensitive to cold within the nasal cavity and other areas of the face relay the information to your brain, and your brain then kicks in to cause bradycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction. As you learned earlier, blood then gets diverted from your limbs and all organs but the heart and the brain, allowing you to conserve oxygen.

The net effect of all these adaptions is that you come up out of the water feeling like a completely zenned out monk. I've talked to guys who have done 10 day silent meditation courses, intense series of transcendental meditation, and brain electrostimulation for changing brain waves…and a few deep freedives get you the same thing.

But that's not the best part of teaching your body to “re-activate” your MDR.

The best part of the dive reflex is a compression of your spleen. The deeper you go, the more your spleen compresses, and when this happens your spleen goes into hyperdrive and injects loads more oxygen-carrying hemoglobin into your blood. This is, effectively, the equivalent of blood doping, a banned method of artificially increase oxygen carrying capacity of the blood by taking illegal drugs or injecting your own blood back into your body. But you get this same effect free (and legally) by freediving.

So freediving activates your body's most primal survival reflex, in a much, much more powerful way than, say, splashing cold water on your face.

3) Spearfishing

Let's start here: I love hunting. I love the experience, the primal nature of it, the exercise, and of course, the fact that I can harvest my own tasty food with a bit of hard work and intelligence.

But hunting with a gun is boring. It's not relatively challenging to be able to harvest an animal that has no clue you're anywhere in the vicinity as you shoot it from 1000, 2000 or 3000 yards away. But archery? That's a different story. I love to bowhunt, to spot-and-stalk, and to hunt an animal from as little as 15 yards away.

Similarly, I love fish.

I love to watch fish, to swim with fish and of course, and to eat fish.

But a day of fishing leaves me about as excited, refreshed and fulfilled as a day of staring at paint dry. I'm simply not a big fan of sitting on a boat or standing on shore casting. That statement is not meant to judge fishermen: it's just the way I am.

However, I would say the rough equivalent of bowhunting on land is spearfishing in the water, and firearm hunting is to regular fishing as archery hunting is to spearfishing. Spearfishing has always intrigued me, and the best, most efficient, most successful spearfisherman are – you guessed it – freedivers (one interesting reason for this, whether you plan on spearfishing or not, is that when you're not all decked out in alien-esque scuba gear, fish actually approach you and swim with you).

Want to see more of what I mean? Check out “Spearing Magazine“, a publication full of spearfishing eye candy.

So it is for each of these reasons that nine days ago, I discovered myself standing, along with four friends who I talked into joining me, on the front threshold of the door of Immersion Freediving in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

———————

Enter Ted Harty.

I and my four buddies knocked on the door of Ted's private home at 8am sharp for the start of our first freediving class, and when Ted flung open the door to greet us, I immediately realized he wasn't one of those super-skinny, mild-mannered freediving guys I'd seen softly speaking in freediving videos.

Instead, at over six feet tall and 230 solid pounds, Ted is a big, bold, loud, extroverted character. He looks like a boxer, and not like a guy who you'd expect to be diving at incredibly efficient oxygen capacity to depths deeper than most human beings have ever ventured.

But it was Ted who was about to open my eyes to a whole new world of freediving, and who I would spend nearly every waking hour of the next ninety-six hours of my life learning every possible closely-guarded breath-holding and deep-diving tactic.

Ted began his underwater career in 2005, as a scuba instructor in the Florida Keys. Over the years, Ted became a Scuba Schools International Instructor and a Professional Association of Diving Instructors Staff Instructor.

But whenever Ted was on the boat and did not have students to take care of, he’d jump in with mask, fins and snorkel and play around on the reef, sans scuba equipment. As Ted highlights in this fascinating, quick video about his life:

“Sometimes I’d have just five minutes to swim around without all of my scuba gear. I loved it. I could swim down to the sand at Sombrero Reef and hang out for a bit at 20 feet. I wanted more. I wanted to learn how to stay down longer and how to dive deeper.”

So, in January of 2008, Ted took his first Performance Freediving International (PFI) course.

“I couldn’t believe how little I knew about freediving at the time. As a scuba instructor I knew more about diving physiology than the average Joe, but quickly realized I knew nothing about freediving. At the start of the course I had a 2:15 breath-hold, but after just four days of training I did a five-minute hold! I couldn’t believe it was possible.”

So next, Ted signed up for instructor-level courses at Performance Freediving. He was soon offered a job teaching with Performance Freediving, when he moved to Fort Lauderdale.

Then, in 2009 Ted went to PFI’s annual competition. At the time, he was about a 80- to 90-foot freediver and weighed 230 pounds. He wasn’t in good shape at all, but after three weeks of training under the tutelage of world-reknowned freedivers Kirk Krack and Mandy-Rae Cruickshank, he did a 54 meter (177 -feet) freedive.

“I was blown away by what I was capable of.”

Ted spent a year working with Kirk and Mandy, while traveling around the country teaching the Intermediate Freediver program. Then, in 2010, a much more fit Ted went back to PFI’s annual competition. That year his new personal best was 213 feet, and currently he's managed to up that to an impressive 279 feet.

In June 2012, Ted was selected as the Team Captain for the US Freediving Team at the Freediving World Championships, and in 2013 he attained PFI Advanced Instructor and PFI Instructor Trainer, becoming the first and only PFI independent instructor to receive this rating.

Oh yeah, and Ted also holds the record for hypoxic underwater swimming in the pool, having done 7 full lengths (175 meters) without a single breath.

But most impressive?

Ted has anemia.

This means his blood can't deliver oxgyen as efficiently to his muscles and brain as most of the world's population. Thes means he has a blood hematocrit level of 34, easily 1/3 less than most athletes. This is a condition that would leave most folks huffing and puffing for air after climbing a flight of stairs.

Obviously, anemia hasn't stopped Ted. And now he was about to share his secrets with us.

————————–

Now, before you discover exactly what Ted taught us, you should know one other juicy, important detail about this freediving excursion, a detail that will especially intrigue the average nutrition nerd.

That detail goes by the word “ketosis”.

See, around the same time I recorded that first freediving podcast I mentioned earlier, I also released an interview with University of Florida researcher and scientist Dominic D' Agostino. In that episode, “A Deep Dive Into Ketosis: How Navy Seals, Extreme Athletes & Busy Executives Can Enhance Physical and Mental Performance With The Secret Weapon of Ketone Fuel“, Dominic highlights his research into the use of ketones to enhance breathhold time and reduce the brain's requirements for oxygen.

Apparently, Dominic's research seems to be suggesting the fact that diet-induced ketosis from a high-fat, low-carb intake, especially when combined with the use of nutrition supplements such as powdered ketones or MCT oil, vastly reduce the need for the brain to use oxygen to burn glucose. This is because the brain can use up to around 75% of its fuel from ketones. So a ketone-fed or a fat-adapted brain can be better equipped to withstand low oxygen availability and potentially support longer breath-hold times. Dominic's research also shows that in the presence of ketosis, the brain and body are able to resist the potential cell damage of long periods of time with low oxygen, also known as “hypoperfusion”.

As I learned in a tortuous lab experiment last year at University of Connecticut (gory details here), a high-fat, low-carb diet can teach and allow the muscles to tap into more fat for fuel, making your body crave less use of oxygen in the large muscles of the legs, arms or other areas that you've learned oxygen gets shunted away from when deep underwater.

A diet low in sugar and starch is also less acidic. This lowers carbon dioxide levels in the body, which could theoretically also increase breath hold time. This is because breath holding is normally terminated due to an urge to breathe that is mostly caused by increasing carbon dioxide levels.

Interestingly, most of the animals that regularly rely upon the mammalian diving reflex are marine mammals. Marine mammals, for the most part, live on almost exclusively fat and protein (e.g. fish) and yet are able to maintain a largely aerobic, (oxygen-based, metabolism – even while holding their breath.

Based on all this, the week prior to my freediving trip, I talked to Dominic and asked him how I could quickly get back into ketosis so that I could maximize my breathhold time and my tolerance to freediving. His reply was simple:

1) Immediately switch to 80%+ fat-based diet…

2) Take 2-3 servings of powdered ketones in the form of “KetoCaNa” per day (Prototype Nutrition was kind enough to give 10% discount with code BG2015)…

3) Use MCT oil or MCT powder liberally in smoothies, teas, coffees, etc…

Easy enough.

So I immediately cut sugar and starches, and shifted my diet to include meals such as fatty fish, walnuts and chia seeds, coconut milk, and copious amounts of decaffeinated “Bulletproof Coffee” (caffeine raises heart rate, so caffeinated coffee flies in the face of becoming a better freediver). Using this strategy, and based on my testing with a Ketonix breath testing device, I achieved a deep state of ketosis (3+ mmol ketones for you quantified geeks) within just 48 hours. Incidentally, this is much more immediate and deeper level of ketosis than I ever achieved in previous experiments sans powdered ketones and high MCT oil intake.

Hooray for science.

Then, armed with a boatload of ketones circulating through my bloodstream and feeding my brain, I delved into Ted's class.

—————————-

Now here's the deal: out of respect to Ted's proprietary system and method of instruction, I'm not going to reveal everything that I learned over 96 hours of intense freediving instruction. However, there were some definite highlights.

Day one…

Ted began by scaring the hell out of us.

For the first three classroom hours of the course, we learned every possible method on the face of the planet to avoid something called “shallow-water blackout”. Shallow-water blackout is a sudden loss of consciousness caused by oxygen starvation, and this unconsciousness strikes most commonly within 15 feet of the surface, where expanding, oxygen-hungry lungs literally suck oxygen from your brain and into your blood.

In other words, you don't usually die underwater. You die on top of the water.

Armed with sheer dread of passing out in the water, we proceeded to the pool for “static” breathhold training. Here are the basics of how to hold your breath for a really, really long time…

…relax by spending several minutes doing ventilation breathwork: 2 seconds in, 2 seconds hold, 10 seconds out, 2 seconds hold, repeat. Just try it. You may get so relaxed that your fingers get tingly. But that's not good. This is because you blow off too much CO2 you will start to have certain symptoms, and tingling in the fingers (along with euphoria and tunnel vision) is one of those symptoms. This is also known as “hyperventilation”, or “overpurging”, and if you start a dive with these symptoms you are putting yourself at risk for a whiteout, which is basically a blackout that occurs in the beginning of a dive.

…next, do five “purges” to blow off carbon dioxide: 1 second in, 4 seconds out. This type of purging can very easily be confused with hyperventilation, and I really don’t recommend you try it unless you’ve had formal instruction in how to do it the correct way, as it can lead the same type of dangerous issues I described above.

…finish with a deep, deep belly breath that you move up to your chest, your shoulders and your neck. You literally take a breath with your entire friggin' body.

Then…plunge your face into the water, relax every possible muscle, and wait for intense urges to breathe, painful diaphragmatic contractions, and a complete body freak-out to occur as you force yourself to zen out while sending your body a message that you've completely cut off its most crucial fuel source: oxygen.

Once you've got that down, you do a similar exercise, but this time you empty all the air out of your body, and then do it upside down. Here is yours truly, demonstrating.

Allow me to make a very, very important point: don't try this on your own. You don't want to get your lifeless body fished out of a pool after you get shallow water blackout by playing around all by yourself with breathholds. And for Pete's sake, don't do it in your car either.

My first breathhold: three minutes. This was without the use of ketones. As a smart little guinea pig scientist, I knew we'd have another static breathhold session the next day, so I waited to use the KetoCaNa and MCT Oil, and spent the rest of the pool sesson learning some very crucial safety techniques.

Day two…

We began with more time in the pool. My body was already morphing into a wrinkled prune from living in the water, and this freediving course wasn't even halfway over.

Breathhold number two, which I attempted 30 minutes after consuming a serving ketones and tablespoon of MCT oil…

…was 4 minutes and 15 seconds. Granted, I'll readily admit that adding an extra minute and fifteen seconds to my breathhold was partially due to becoming more comfortable with the training and partially due to my mammalian dive reflex kicking into hyperdrive. But I also highly suspect that ketosis helped.

After the morning pool session and a brief stop a sandwich shop, we headed to the ocean, where I was about to experience one of the most frustrating times of my entire sporting career (for those of who question the high-fat, ketotic virtues of a sandwich shop, please don't freak out too much: I ordered the tuna salad wrap and dumped my tuna out of the wrap).

Now allow me to clarify something: I've hammered through 5K open water swim competitions, hundreds of hours swimming in the surf, and freezing nights in the ocean during the brutal SEALFit Kokoro camp, but in my entire life, I've never ventured more than fifteen feet below the surface of the ocean.

Nonetheless I felt ready. After all, Ted had taught me the “Frenzel technique” of equalization, and I'd been practicing it quite a bit on dry land. It basically goes like this:

-Pinch your nose and close your mouth…

-Close off your epiglottis (you know you are doing this if when you breathe out with a wide open mouth, you can stop the air)…

-Seal your mouth even further by performing a T-Lock (using your tongue to seal the mouth shut along the gum line just behind and above the teeth)…

-Use the muscles in the throat, cheeks and the tongue to compress the airspace you have created. You can push the tongue up inside the space, making a K-Lock (the movement you make when you say the letter K)…

-Ensure that your soft palate is open and neutral to allow the air which you are compressing to reach the openings of the sinuses and the eustachian tubes. The soft palate is open when its relaxed. Play with this sensation by feeling it move up and down when you either blow out through pursed lips (up position, not what we want), and when you breath out through your nose with an open mouth (down position, also not what we want). During this process find the neutral point, as this is what you need to leave it in while diving…

-Allow the air which you are compressing to fill the air spaces in your ears and sinuses…

-When you are doing this on dry land (with a half pinched nose) you should hear and feel a puff of air come out of your nose. You should also see the front of your upper neck area move up and down as you do this…

-You will need to re-load your mouth after you descend further, so practice filling your mouth with bits of air, then closing your epiglottis…

-Practice the whole technique with empty lungs so you know you are not cheating and compressing air directly from the chest and stomach, which shouldn't move at all…

Easy, eh? Now, do all this upside down while hovering over a six hundred and forty foot deep ocean.

You get the picture. And I failed. Big time.

On my first ocean dive, I made it to a grand total of twelve feet. Then I spent nearly two minutes at that depth, making frustrated, desperate attempts to equalize so that I didn't rupture my precious eardrums. I came back to the surface sputtering, spitting and very disappointed in myself.

On the next attempt, I made it to thirteen feet. At this rate, I'd get to the magic first-day-in-the-ocean goal depth of thirty three feet after an impossibly daunting number of dive attempts.

Still no dice.

Third attempt? Fifteen feet.

Not only was I was getting more and more frustrated that I couldn't equalize my ears, but I was getting seasick, blowing blood out my nose, and seeing sharks. Yes: sharks. Florida is the shark-bite capital of the world, and now my blood was floating around in the ocean, along with bits of tuna fish sandwich I was puking up.

Not a good day. I got back on the boat determined to practice my Frenzel equalization 500 times that night, while hanging upside down off the edge of my bed.

Day three…

I woke up bleary-eyed, exhausted and keeping my fingers crossed that the day would go better. We spent the entire morning in Ted's classroom, learning the physiology of freediving, the physics of freediving and even the psychology of freediving, including how to voluntarily shut down our “fight-and-flight” sympathetic nervous system, visualize, decrease our heart rate, kick more efficiently and much, much more.

Then, after skipping the dreaded sandwich and opting instead for more ketones and oil, I headed back to the thirty-minute boat ride out to the middle of the ocean with the rest of the class.

The rest of the day didn't go much better. This time, I made it to barely twenty feet, but only on the very last dive, and again with over two minutes of underwater struggling and frustration, and not the peaceful deep blue calm I had been hoping for.

See, voluntarily relaxing your fight-and-flight nervous system and doing perfect equalization to dive is easy in a dry-land classroom. But it's not so easy when you tear down the classroom, throw it in the ocean, then surround it with shark sightings, along with stinging jellyfish floating dangerously nearby and enormous swells drifting you seven miles out into the ocean.

At the end of day three, I posted this exasperated photo to Facebook:

Note the caption:

Bleeding nose, torn up eardrum, on the fence about another day in the ocean…free diving is hard work!

I collapsed into bed, once again exhausted, disappointed in myself, worried about my ears and nose, wondering if I had brain damage, and finally drifting off to a fitful night of sleep.

Day four…

Day four promised to be the biggest day yet.

The plan? Spend the entire day in the ocean, practicing dive after dive after dive until we perfectly nailed eighty-four feet. I sat on the dock listening to Ted outline this plan, internally dreading another day of frustration in the water.

Before heading out into the ocean, we learned what Ted described as the secret sauce of every good freediver, an awkward, stomach-sucking pose in which you exhaust every last bit of oxygen from your body, then hold your breath in a crawl position as your body goes into painful, involuntary spasms. Ted described that this is how he begins every day, and suddenly my morning deep breathing and yoga routine seemed very ho-hum.

We headed back out onto the ocean. On dive one, I made it back down to twenty feet, then once again simply writhed and struggled in the ocean, attempting to equalize.

I came up for air. The sky was overcast and grey. But the water was eerily calm. There was still time for more diving.

On dive two, something clicked. Perhaps my mammalian dive reflex kicked in. Perhaps my sympathetic nervous system was finally responding to my ventilation practice. Perhaps my body's neuromuscular system was finally learning to relax. I made it to forty-five feet, turned, smiled at Ted's camera, and returned to the surface, where the rain was lightly falling.

Eighty-four feet still seemed far away, but forty-five feet was progress, and over three times deeper than I'd ever gone in my life.

On the next dive, I ventilated for five minutes…

Two in, hold two, ten out, hold two.

I purged…

One in, four out, one in four out, again, again, again.

I took my deep breath…

Belly, chest, shoulders, throat, suck, suck, suck, equalize, go.

I dove with my eyes closed. Fifteen feet. Then thirty feet. Forty-five feet passed by. Then sixty feet. And then, at a tranquil, peaceful beautiful blue depth of sixty-six feet, I did an underwater fist pump, and kicked back to surface with plenty of air to spare and a big smile on my face. I was actually learning to freedive.

I surfaced to loud shouting, hand waving, a churning sea, and this dark black sky I photographed with my phone:

Ted checked the weather radar, and it revealed funnel clouds. Yep, that means tornado-warning for you Western-state folks. The boat captain was waving his arms and yelling at us to immediately get in the boat, and I wasn't about to hesitate.

I swam like hell to the boat, pulled myself in, and then spent the final hour of my freediving course holding on for dear life as the boat motored back twelve miles to shore in lighting, pelting rain, dark thunderclouds and extreme gusts of wind.

Eighty-four feet would have to wait, but when it comes, I'll be ready.

————————-

So what did I discover in this adventure?

First, and quite interestingly, I've learned the body can massively increase breathhold time through a combination of mammalian dive reflex activation and some very probable help from ketones. I'm staying in ketosis indefinitely as I continue to experiment with the new supplements and testing techniques that make it far easier to hack one's way into high-fat dieting.

Second, after countless hours of breath-counting, ventilation, breath-hold, inhaling slowly, exhaling slowly and nasal breathing, I've developed enormous amounts of patience. The day after the freediving course ended, I went on a sixty minute run while breathing through my nose the entire time, and felt afterwards as though I'd finished a relaxing yoga class. The next day, I ventured into the gym, lifted weights with the same technique, and was shocked when I looked at my watch and saw that I'd spent ninety minutes working out with calm, patient focus. I've discovered a whole new approach to breathing for cortisol lowering, for workout focus and for daily patience that gives me monk-like perseverance in the face of extreme heat, extreme cold, extreme depths and extreme stress. And I've even downloaded an apnea app to my phone to practice full-body writhing breathholds while I watch Hulu.

And perhaps most importantly, I've learned how to activate and control the most primal reflex known to man and the reflex that Olympic athletes around the world are now pursuing: the mammalian dive reflex.

————————-

What's next?

Stay tuned for a detailed podcast with Ted Harty coming soon, in which Ted and I will reveal many of the tactics I breezed over in this article, tactics that will help you whether you want to manage stress better, become a better athlete, increase your blood oxygen levels, or freedive. In the meantime, you can check out Ted's classes at ImmersionFreediving.com.

Stay tuned for a follow-up Q&A article to reply to the many questions I've been getting about ketosis and ketones.

And of course, stay tuned to my Instagram account in the near future for some entertaining spearfishing photos.

In the meantime, do you have questions, comments or feedback about free-diving, breath-holding, ketosis, spear-fishing or more? Leave your thoughts below and I promise to reply.

—————————

The main reason I love free diving is for the adventure, you don’t know what it may happen or what you may found below the water surface. In the past years I’ve taken a lot of pictures of the marine life which I store in the https://dive.site logbook, along with all my diving logs. It’s cool that I can also search new dive spots or even add my own.

Breathology by Stig Severisen is a pretty good book. Stig has done some pretty amazing stuff, lots of world records. May be a good guest on your podcast. Thanks for sharing.

Ben,

Sorry I double posted that. Had to edit my account and I guess it posted my comment twice. Thanks for the response.

Best,

Daniel

Ben,

I just got done training with Wim in Poland and I'm looking to gain as much experience as I can with cold thermogenesis and breath holding. Unfortunately, I live in NYC and don't have a lot of travel opportunities(Wim was an exception) due to vacation time and money. Any schools in the NYC area you can recommend?

Ben,

Just got done training with Wim in Poland and am really trying to gain more experience(and eventually expertise hopefully) in breathing/meditation techniques and cold thermogenesis. Unfortunately, I’m stuck in NYC and don’t make much money so travelling to do the course in Ft. Lauderdale might be a little tough. Do you have any recommendations to learn freediving in NYC?

Awesome article!

Daniel

Ted may know. Contact him through his website and ask!

Great experience, Ben. Swim coaches often do hypoxic sets and I’ve felt it is probably not good for cognition to intentionally deprive your brain of oxygen, especially if you’re older, 69 in my case. Are you aware of any research in that area?

Short term, brief hypoxia is actually GOOD for your brain, not bad. It's long term hypoxia you need to worry about (e.g. sleep apnea, living in polluted areas, stuff like that)

Awesome write up, Ben, especially after recently reading Steven Kotler's Rise of Superman, recognised a few names

Hey Ben! What a cool experience. Definitely on my list to do! I'd be curious to know what your eating style will be from here on since you mentioned about staying in ketosis indefinitely. Will you still do the carb cycling where you eat a high fat diet then add more carbs later in the day especially post workout? Looking forward to the podcast with Ted. Keep up the awesome work!

Thanks!

-Matt-

Yep, I'll basically be doing cyclic ketosis, I'll just more intelligently use BHB salts, Brain Octane, etc.

Hi Ben, seems like you had a great experience! I was listening to your interview with Yuri on his summit. You talked about hypothermia & brown fat, and there you also mentioned about generating new brown fat cell if on a caloric surplus. So my question is, aren't we going to gain some fat anyway being on a surplus, in this case, wouldn't brown be better than white? Or will it accelerate the rate which you gain fat cos now you're gaining both brown & white? Also, what about someone already having some body fat (like 12-15%) on a slight surplus? Will our body try to convert white to brown or will we just start making more brown?

Thank you sooo much :)

Well, if you're going to add more fat, brown fat is definitely better, but if you're trying to maintain or lose weight, then simply use cold thermogenesis but don't eat a caloric surplus and you can have white fat to brown fat conversion without excess formation of *either* type of fat.