May 20, 2013

In case you didn't notice, it's been a little while since I published a chapter of the book I've been slaving away on: Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance, Health & Life.

There's a good reason for this.

See, my goal in life is to help you achieve your dreams, and to teach you how to be healthy on the outside and healthy on the inside while achieving those dreams.

But last week, I found out some pretty disturbing things about my stress levels. And I realized that I need to slow down a bit. To pull my own parachute, so to speak. And it'd be pretty ironic to write a book about how to achieve the optimal balance of health and performance if I wasn't really following my own rules, would it?

So I slowed down.

OK, OK, maybe I procrastinated a little bit too. C'mon, YOU try churning out a book.

But in the meantime, I do have some really good news. I've finished another section of the book for you! Check out the video below, then keep reading to learn how to make grimacing, ugly faces just like me. And remember – you and I are writing this book together, so be sure to leave your feedback, comments or suggested edits below, and I promise to reply.

—————————————

Mobility

The section of “Beyond Training” you're about to read addresses a key component of endurance that I've found to be sorely neglected (pun intended!) in the training of nearly every individual on the face of the planet. If you pay attention to what you're about to learn, you're going to absolutely change your life by changing the way your body feels 24-7, forever.

The topic we're digging into today is mobility – namely the way your joints, tendons, ligaments, appendages and body moves.

After all, no matter how much of those first three essential elements of strength, power or speed you've built, you're going to find that your joints slowly degrade, your body gradually falls apart, and you move like an awkward stork unless you also optimize your mobility.

Let's begin with an example…

————————————–

Why Mobility Matters

During the days that I was working on this chapter, I raced the Wildflower triathlon festival in California. Not only is this one of the toughest courses on the planet, but it includes brutal, joint-pounding downhill stretches on the run course that can leave your areas such as your hips and low back “locked up” for days.

As a venture into masochism, I actually signed up for Wildflower Half-Ironman on a Saturday, and the Olympic distance race on a Sunday (read more about this brutal experiment here and read more about the body damage that ensued here). This meant I had less than 24 hours to recover between two very tough races.

But to my panic and dismay, I woke up on Sunday morning with a completely immobile left hip, experiencing sharp pain deep in the hip joint with every step. And no matter how much frantic stretching and leg swinging I did in the last precious hours leading up to that second race, the pain simply wouldn't diminish, and I limped about like an awkward stork as I prepared for the race, wondering if I'd even being able to actually race.

It wasn't until I visited an “Active Release Therapist” (just one of the mobility techniques you'll discover shortly) at the race expo that I was able to get a practitioner to dig their elbow into the side of my hip, do a few simple pressure point and mobility tricks, and make me 100% mobile and pain-free for a fantastic race.

That's how mobility works.

It's not necessarily all about stretching, flexibility, range-of-motion, or whether you can touch your elbow to your nose. As you're about to learn, those activities can sometimes make your movement and pain problems worse. So it's time to learn exactly what mobility is (and figure out how to not be that stork).

—————————————-

Essential Element 4: Mobility

Mobility refers to your ability to move your body and limbs freely and painlessly through your desired movement.

And because we endurance athletes tend to prioritize “conditioning” and ignore activities that don't make us breathe hard or feel the burn, mobility is possibly the most neglected basic ability in an endurance training program, especially for a high-volume athlete such as an Ironman triathlete or marathoner.

Just think about it. Nearly all endurance training takes place in some kind of chronic repetitive motion pattern that:

1) Has limited joint range-of-motion, such as sitting bent over on a bike for multiple hours, running at a relatively slow speed that never allows full hip extending or knee flexing, swimming for a long time in a freestyle position, etc.

2) Takes place in a single, front-to-back plane of motion – with very little sideways “lateral” movement, aside from the occasional swerve to side-step dog poo or roadkill.

3) Involves forces applied in only one direction. For example, a freestyle swimmer engages in repetitive internal rotation of the shoulder, but very little external rotation of that same shoulder. And a cyclist or running engages in repetitive hip extension against the pedals or the ground, but when it comes hip flexion, tends to flex the hips against a relatively low resistance (e.g. lifting the leg up with just the weight of the leg itself, without having to fight the force of the pedal or the ground).

Based on these three factors, it's no surprise that weakness and tightness tend to be prevalent in most endurance athlete bodies. Time and time again I have taught camps, clinics and seminars during which athletes who could hammer like animals on the bike all day long or run stone-faced for hours on end simply can't do something as simple as a full squat with both arms held overhead, or even a basic, proper push-up.

As a result, despite decent fitness, these folks – and most of us endurance athletes – are predisposed to all of the disadvantages that accompany this lack of basic mobility, including:

-Muscle tightness that creates ugly postural imbalances – such as shoulders rolling forward in a hunchback pattern, hips rocking back (to create that nice skinny-fat beer-belly look), and one side of the body being higher or lower than the other side. This results in leg and arm length discrepancies, not to mention funny looks when you're wearing a swimsuit, tight clothing or anything else that reveals your body asymmetries. Aesthetic annoyances aside, these are also huge issues when it comes to injury risk. So you look weird and you get hurt easy. Not fun.

-Soft tissue, muscle, fascia and tendon restrictions such as extremely tight IT bands (on the sides of the thighs), tight and immobile rotator cuffs in the shoulders and restricted neck and upper back muscles. Any of these can make even a young, spry marathoner move like an 80 year old man when doing anything other than jogging. When teaching triathlon clinics, I've had groups of triathletes lunge across a room with medicine ball held overhead – and they suddenly looked a lot more like baby deer on ice than like athletes.

-Joint capsule restriction in the knees, hips and shoulders. Each of your joints are surrounded by a fibrous tissue sac called the joint capsule. This capsule surrounds the joint and is filled with a fluid called synovial fluid that lubricates your tissues and the spaces within this capsule. When the joint capsule is immobile, fluid can build up in the joint and the tissue can't move properly, meaning you're predisposed to premature cartilage breakdown in that joint, along with nasty meniscal tears, sharp pains and “catches” in your joints, swelling, inflammation and everything else that simply can't be permanently fixed with an ice pack, an ibuprofen and a trip to your favorite massage therapist.

-Muscular restrictions and faulty movement patterns. It's not just your joints that get restricted. Since your muscles themselves are comprised of fiber and are surrounded by a spiderwebbish sheath called fascia, immobility in this soft tissue can also cause some serious movement deficits. This includes shoulder blade (scapular) and middle back (thoracic) immobility that leads to shoulder pain while swimming, hip extension immobility that leads to lower back pain on the bike and hip flexor immobility that leads to calf pain and inner thigh pain on the run. Yes, that means that you can address propensity for Achilles tendonitis or plantar fascitiis by simply standing up every hour from your desk and stretching tight hip flexors or foam rolling tight quads.

-Overworking of muscles. When a joint is immobile, the joint above or below that immobile joint is forced to take up the slack or significantly assist with a motion it's really not suited for. Just picture the common scenario of a runner's or cyclist's knee doing weird sideways movements instead of hinging forwards and backwards. This happens because an immobile hip is stuck in constant external rotation, and as a result, most of the hinging must be accomplished by either the knee joint or the low back joint. This places undue and unnatural strain on these areas. Of course, an unsuspecting athlete might simply try fixing the knee or fixing the low back, without ever actually rescuing the hip from that external rotation.

-Loss of movement economy and efficiency. Multiple studies have found that when mobility decreases, economy also decreases. This one makes perfect sense, especially if you've ever watched a swimmer with tight hips and limited shoulder mobility zig-zag from one end of the pool to the other. Studies back this up. For example, (11) found that when hip flexion and hip extension mobility was optimized in runners, there were also noted improvements in running economy. Other studies (3, 10, 17) have found that when these same hip muscles are mobile, both economy and force production goes up, especially over long running distances. In swimming, mobility may be even more important to economy than in running and cycling. For example, Jagomagi and Juramiae (16) found that shoulder mobility was responsible for nearly 30% of the performance variability in swimmers, and Silva (24) found that ankle and trunk mobility were two of the most predictive variables to 200 IM performance. Here's the kicker: mobility in this areas turned out to be even more important than threshold fitness and the body's ability to buffer lactic acid.

Let's face it: it's a pretty frustrating scenario to gut things out for months of solid training, possess a huge cardiovascular and metabolic engine, build an enormous number of well-firing muscle motor units, but arrive at the starting line of your race with a complete inability to be able to even halfway tap into your fitness because you simply can't move through a necessary range-of-motion. What a waste.

My most painful memory of this was being forced to walk a 6 hour marathon at Ironman Hawaii because I didn't pay proper attention to my hip mobility (see the picture of me on my long death-march). What about you?

But with a few simple mobility drills worked into the weekly routine, this could all be avoided. Let's learn how.

—————————————-

Training Strategies For Increasing Mobility

So increasing mobility should be easy – you just need to stretch more…right?

Man, oh man – I wish. Now don't get me wrong: I personally stretch every single morning for about 10 minutes, using a series of basic yoga moves and doing some deep diaphragmatic breathing. This kind of “stretch-and-hold” activity is called static stretching.

However, I don't start off my day with static stretching because I think it's somehow to help me with mobility. Instead, it’s just a very relaxing way for me to start my day. Static stretching actually slows down the body’s sympathetic, “fight-and-flight” nervous system, which can be beneficial for decreasing blood pressure, controlling stress, helping with focus and making you feel generally good.

But static stretching really doesn't help much with mobility, and worse yet, when you're mixing it up with a workout or race, it can significantly hinder your performance potential. For all intents and purposes in the goals of most endurance athletes, stretching is dead.

For example, a recent study on runners (18) found that when runners were on average 13 second slower when they performed static stretching immediately prior to a 1 mile uphill run. So much for those toe-touches before you go tackle the hill repeats. In fact, multiple research studies (2, 14)have shown that static stretching can inhibit the amount of force that a muscle can produce and limit physical performance in just about any jumping, running or lifting activity you may be doing after that stretching session. And further data (13) has shown that static stretching doesn’t even reduce your risk of injury, which is one of the primary reasons that you may have been led to believe you should do static stretching before exercise.

The New York Times recently reported on two new studies that continued to prove the detrimental effects of static stretching pre-workout (9, 22). The first study showed strength impairments in people who performed static stretching before lifting, compared to those who performed the type of dynamic warm-ups you'll learn in just a bit.

The second study looked at a total of 104 previous studies on stretching and athletic performance, and found that in almost every study – regardless of age, sex, or fitness level – static stretching before a workout decreased performance. This all comes down to the fact that making muscles loose and making tendons too stretchy prior to exercise makes these soft tissue components less above to produce quick and powerful responses.

Think about it this way: when you're static stretching, you're doing the complete opposite of what you're trying to achieve through plyometrics – explosiveness!

This is because stretching is not mobility.

But that's not the only issue with stretching. If your body is already messed up or injured, stretching can actually create more problems than it actually fixes.

For example, if you're genetically prone to hypermobility, too much stretching can make you – drumroll please – too stretchy. This excessive joint laxity is a bigger issue in females and younger populations, and in Clinical Applications of Neuromuscular Techniques: Volume 1, it is noted that joint laxity can also be much higher in people of African, Asian, and Arab origin. Joint hypermobility and the ability to hyperextend may make for a cool double-jointed party trick to show your friends, but can mean less force production potential and increased risk of cartilage and bone injury.

Here's another drawback to static stretching: when you're exercising frequently, your muscle fibers can easily get cross-linked, knotted and stuck to one another in a pattern called an adhesion. Now think of these knots in your muscle as a rope with a knot in the middle. If you pull on both ends of the rope, what happens? The knot gets tighter, and more difficult to untie. This is how static stretching can make things worse if you have poor mobility, adhesions, knots and other “tissue issues”.

So hopefully you're getting the idea that you can't just stretch, and I'll say it one more time: stretching is not mobility. About the only time when static stretching comes in handy for an endurance athlete is A) to relax and assist with blood flow after the workout; B) to lower stress or increase focus at the beginning or end of day (such as the yoga, meditation and deep breathing that I personally do); C) to relax muscles that tend to tighten and spasm during very long periods of time in a shortened position (e.g. doing a long stretch for your hip flexors prior to a 100 mile bike ride).

In contrast to static stretching and traditional flexibility exercises, true mobility actually addresses all the other elements you just learned about – not just short and tight muscles, but also other soft tissue like tendons and ligaments, joint capsules, neuromuscular recruitment, movement dysfunction, and muscle recruitment issues.

So how do you increase mobility?

Instead of static stretching, there are three primarily mobility enhancing strategies that you can easily learn and incorporate: dynamic stretching, deep tissue work, and traction.

———————————-

1. Dynamic Stretching

I personally do a dynamic stretching session before (or a few minutes into) any run. I also do about 5-10 minutes of dynamic movements after each of those yoga/meditation sessions that I do each morning.

Dynamic stretching, also known as ballistic stretching, is a stark contrast to static stretching in terms of its ability to adequately prepare you for a workout session or improve mobility, and studies have shown (22, 23) that dynamic stretching can improve power, strength, and performance during a subsequent exercise session.

When you're dynamic stretching, you're not just “pulling on” a specific muscle group like you do when static stretching. Instead, dynamic stretching, incorporates posture control, stability, balance, and even ballistic and explosive movements such as swings and kicks.

Here’s a good example.

With your right hand resting on a wall, use your left hand to pull your left heel to your butt. This is a traditional static quadriceps stretch.

Now, step away from the wall, take a giant lunging step forward with your right leg, use your left hand to pull your left heel to your buttock, and then release, take a giant step forward with your left leg, and repeat for the opposite side. That's a dynamic version of the same quadriceps stretch – and suddenly your quavering, balancing, focusing and moving the muscle all throughout the stretch. Because you're improving stability, balance and mobility while also actively contracting the muscles, the latter example is a far superior method of stretching.

There are many, many ways that you can dynamically stretch, but any dynamic stretch session is typically comprised of basic movement preparation patterns such as lunges, squats, swings and movements of of joint and muscle through a variety of movement patterns. Here are five good dynamic stretch moves to get you started. Try these before your next workout, or just after you've warmed up:

1. Leg Swings:

Hold on to a wall, bar or anything else that adds support, then swing one leg out to the side, then swing it back across your body in front of your other leg. Repeat 10 times on each side.

Keeping your back and knees straight, walk forward and lift your legs straight out in front while flexing your toes. For a more advanced version, you can do this with a skipping motion. Walk for 10-20 yards.

Step forward using a long stride, keeping the front knee over or just behind your toes. Lower your body into a lunging position by dropping your back knee toward the ground. Then push forward, take a giant step, and repeat for the opposite leg. To make this motion even more effective, twist and look back towards the leg that is behind you once you’re in the lunging position.

Stand with your feet wide apart, then extend your arms out to the sides and bend over, touching your right foot with your left hand. When you’re bent, keep your back straight and your shoulder blades pulled back. Then rotate your torso so your right hand touches your left foot. Keep both arms fully extended so that when one hand touches your foot, the other hand is pointing to the sky. Keep rotating like this for 20-30 repetitions.

Stand with your feet shoulder width apart, and your arms held out in front of your body. Then drop as low as you can, pushing your butt out behind you, keeping your knees behind your toes and swinging your arms back. Stand and bring the arms back to the starting position. Complete 10-15 deep squat repetitions.

Just like a rubber band, a muscle is always more pliable and when it is at a higher temperature, so if you want to train your body to move through a greater range of motion during your dynamic stretching, you can do 5-10 minutes of light cardio before doing dynamic stretching. In other words, if you don't want any snapping to take place, don't get too ballistic with if your muscles are cold rubber bands.

The list above is by no means comprehensive. In my own quest to constantly challenge my brain with new moves, I personally vary my dynamic stretch routines all throughout the training year based on good dynamic routines I stumble across on various websites and in magazines. There are other fantastic resources on dynamic stretching in articles such as this on TrainingPeaks or this article on Runner's World, the Resistance Stretching DVD with Olympic swimmer Dara Torres, and the free routines available at CorePerformance.com.

———————————-

2. Deep Tissue Work

“Deep tissue work” is my umbrella term for any type of stimulation that works deep into your muscles and connective tissue, such as the Active Release Therapy I alluded to earlier when describing my Wildflower triathlon hip experience. Deep tissue work also includes some of my other favorite mobility-enhancing techniques, including Rolfing, Muscle Activation Technique, Advanced Muscle Integrative Therapy, Graston, Trigger Point Therapy, deep tissue sports massage, foam rolling, and even simply using a tennis ball, lacrosse ball or golf ball to dig into tight or sore spots.

When your body has chronic tightness and tension or an area with a history of injury or overuse, there are usually adhesions (bands of painful, rigid tissue) that form in the muscles, tendons, and ligaments in that area. These adhesions can block circulation and cause pain, inflammation and limited mobility.

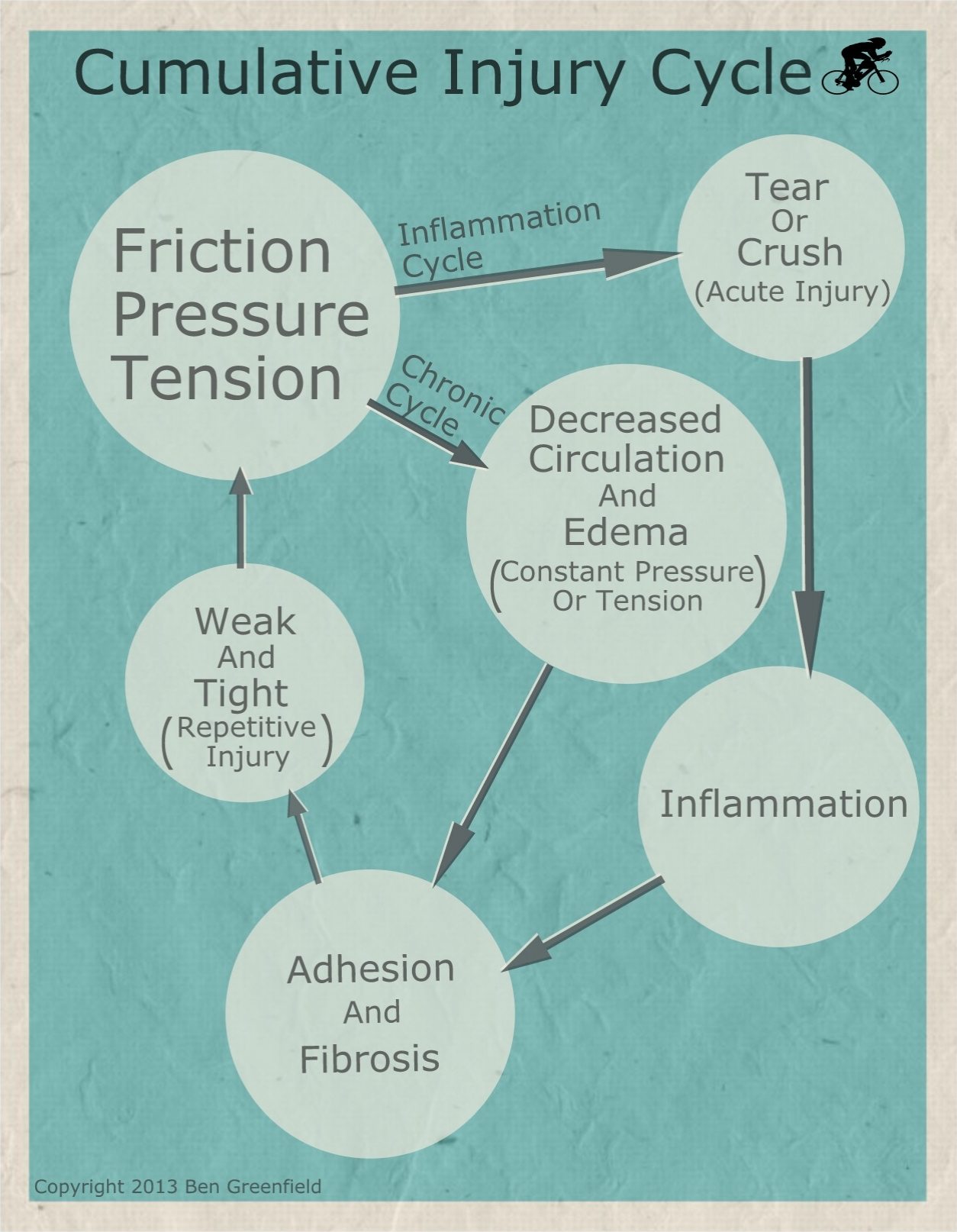

In sports medicine, this is referred as the “Cumulative Injury Cycle” and it looks like this:

In the Cumulative Injury Cycle, a repetitive effort (such as sitting) causes muscles to tighten (such as your hip flexors). A tight muscle tends to weaken and a weak muscle tends to tighten, which creates a vicious pattern. As the muscle become tighter and tighter, the area of tension experiences higher amounts of friction and pressure, which increase potential for injury and inflammation.

This friction and pressure can happen even in the absence of an external force. In other words, you can create this scenario by sitting all day, and it doesn't necessarily require a barbell squat or long bike ride. As tightness in tissues increases, this decreases circulation, resulting in even more swelling, less flow of blood and lymph fluid to the area and further pressure and tension. The lack of oxygen (cellular hypoxia) from this restricted circulation can cause even more fibrosis and adhesions to occur in the tissues. Eventually, a tear or injury occurs, and this restarts the adhesion process.

This is where deep tissue work comes in – it is simply the act of physically breaking down these adhesions, usually with direct deep pressure or friction applied across the grain of the muscles (19, 8). At the same time that adhesions are broken down by deep tissue work, blood and lymph flow to the affected area is enhanced.

When it comes to deep tissue work, different strokes work for different folks (quite literally), but the following is a list of some of the more effective methods that I've found to be the most potent for increasing mobility or reversing pain and injury in endurance athletes:

–Rolfing: Compared to the other deep tissue methods, rolfing (aptly named after unlucky dude by the last name of “Rolf”) focuses almost exclusively on your fascia. During a typical rolfing session, you lie down and get guided through specific movements during an initial “structural integration” session. Your Rolfer then manipulates your fascia over a course of ten 60- to 90-minute sessions. I question whether the ten session is more of a business model than a therapeutic necessity, but if fascial adhesions is your problem, then rolfing is a great solution.

–Advanced Muscle Integrative Technique (AMIT): AMIT is something I first talked about in my podcast ““Dr. Two Fingers” Reveals His Teeth-Gritting, Body-Healing Secrets.“, in which I interview the guy who invented AMIT. AMIT is based around the fact every tissue in your body is saturated with proprioceptors, which monitor and control every aspect of your body’s function. This complex system of receptors monitors tension, pressure, movement, stretch, temperature, energy fields and compression. If you get injured or have a high amount of inflammation in a certain area, these receptors become protective, and shut off function or mobility in that area. Interestingly, sometimes a lack of mobility in an area is due to a muscle near that area being injured (such as a quadriceps injury resulting in lack of mobility in the hamstring). AMIT is based on restoring proprioception by applying deep pressure on specific proprioceptive areas of the body. And as alluded in the title of the aforementioned podcast, it is a bit uncomfortable. But it's also highly efficacious if your lack of mobility is due to a previously injured area.

–Muscle Activation Technique (MAT): MAT is based on the same concept as AMIT. But rather than improving mobility via pressure or kneading, MAT begins with a series of range-of-motion (ROM) testing, followed by specific exercises (usually isometric exercises) to address any deficient areas of ROM. For example, For example, if after a long time riding a bike, you might find that your neck and head gets “stuck” in forward position. So a MAT therapist might then fix that by having you do an look up and perform an isometric contraction with your head backward to try and bring you back to center.

–Graston Technique: Graston employs a collection of six special, shaped stainless steel tools to palpate your muscles and tendons. Although they look like something out of a medieval torture chamber, the curved edge of the patented Graston instruments allow them to mold to different contours around your body. This allows for ease of treatment, minimal stress to the your therapist's hands and maximum tissue penetration. Graston actually comes in quite handy if you're trying to break down scar tissue from injury and or get rid of knots from muscle overuse – and although getting your IT bands “scraped” may sound painful, I've had many athletes get a nearly instant cure from the use of Graston.

–Trigger Point Therapy (TPT): Trigger points (AKA muscle knots) are hyperirritable spots in your muscle that you can usually feel to be tight, taut or hard. TPT is based around the idea that states pain frequently radiates from these points of tenderness to broader areas, sometimes distant from the trigger point itself (such as a trigger point in your underside of your armpit referring paint to the front of your shoulder). By applying pressure to these knots, you can release the pain and restore the mobility. There is actually a Trigger Point Therapy store where you can get instructions, along with special shaped rollers and other devices for doing your own TPT.

–Deep Tissue Sports Massage: In the podcast episode “How Quantum Physics Can Heal The Body and Enhance Performance“, I interviewed my favorite deep tissue sports massage therapist on the face of the planet – a guy named Herb Akers, from Sacramento, CA. Herb runs the website Rules of the Matrix, and calls his special flavor of deep tissue work “Quantum Connective Healing”, in which he combined nutritional therapies, breathing and deep tissue massage to restore mobility or eliminate injuries. Deep tissue massage is designed to relieve severe tension in the muscle and the connective tissue or fascia, and unlike Swedish massage or some of type of relaxing massage therapy, it focuses on the muscles located below the surface of the top muscles. Pressure is applied to both the superficial and deep layers of muscles, fascia, and other connective tissue structures, and these sessions are way more intense than just about any other form of massage you've ever experienced (I usually cry like a baby when Herb works on me). But despite the come-to-Jesus moments you'll experience during deep tissue massage, it is damn effective at restoring mobility.

Here's the best part about deep tissue work: if you don't the time or money to hunt down any of the techniques above, but if you have a willingness to learn and the self-motivation to put yourself through a little discomfort, you can do much of this yourself (7). I personally used to get in a car and drive to a massage therapist every single week until I learned how to do my own therapy with a golf ball, a hard, ridged foam roller I have a love-hate relationship with (a Rumble Roller), a series of lacrosse balls strung together (a Myorope) and rolling-pin like device (a MuscleTrac). Now I only need to see a therapist when I've run into a big mobility issue that I simply can't fix myself, which only happens about 1% of the time.

If you're game to take charge of your own mobility, a fantastic “cookbook” for learning self deep tissue work (and a book that I highly recommend every athlete own for any aspect of mobility enhancement) is “Becoming A Supple Leopard” – written by physical therapist Kelly Starrett, who also has an excellent website at MobilityWOD.comf. In the book, Kelly goes into self-deep tissue work methods such as pressure waves, contract and relax, banded flossing, smash and floss, paper clipping oscillation, voodoo flossing, flexion gapping and a ton of other highly effective techniques that can literally make you bulletproof from injury, but only require simple items such as a lacrosse ball or a barbell.

If you want a taste of the type of mobility movements in Supple Leopard, then go to MobilityWOD.com, check out this great list of mobility WOD's specifically designed for endurance athletes. visit the mobility section of AllThingsGym.com, or read this article on Self My0fascial Release Exercises For Runners.

Be forewarned that deep tissue massage is not a comfortable, relaxing experience. If you decide to hunt down a therapist skilled in any of the methods described in this chapter, you'll typically find that there is no lotion or oil involved, no “Hands of Serenity” posters on the wall and no relaxing chimes music piped into the speakers. The pressure and friction that deep tissue work involves can be teeth-grittingly intense, and you may need to incorporate birthing mommy breathing techniques to get you through a session. I've been known to sob and whimper like a baby, even when it's just me, my immobile hip, and a seemingly innocent and harmless lacrosse ball.

You should also be prepared for the possibility of soreness after deep tissue work, because as the pressure breaks up adhesions and introduces friction into an affected area, your tissues will probably get the same type of inflammation-related fluid accumulation as you get when your lift weights or run downhill – and although this fluid accumulation is temporary, it can cause some pressure and discomfort. I personally control the soreness by taking a cold shower, flushing the body by drinking generous amounts of water and slathering magnesium oil on the area that's been worked on.

———————————-

3. Traction

The final training strategy for increasing mobility is traction.

Traction is the application of a force to the body in a way that separates and elongates the tissues surrounding that joint. Although you'll most often find chiropractic docs, osteopaths, or physical therapists applying traction to patients, you can also traction yourself if you know what you're doing.

Look at it this way – you can change the integrity of your fascia muscle, and connective tissue with deep tissue work and you can increase range-of-motion with dynamic and static stretching, but with either of those techniques, you aren't achieving diddly-squat for the actual bony, capsular area of the joint itself.

This is because your joints are under constant tension from all muscles, ligaments and tendons that surround them, and they are constantly under the effect of these compressive forces. This causes the bones in that joint be closer proximity to each other at all times, and especially during the times when the muscles, ligaments and tendons are tight – which is often the case in just about any active individual. Similar to the “tightening a knot in a rope” analogy, stretching a tight muscle just applies more pressure to the joint which brings the bones even closer together.

And if the bones in your joints are snug and really close to each other, it can completely take away the mobility available in that joint. The lack of mobility limits the ability of the joints to glide in a smooth and frictionless way, so even if the muscles, fascia and connective tissue is mobile, the joint still doesn't move properly.

This is actually how many active people get joint breakdown and osteoarthritis – muscles that move and joints that don't.

But traction is a great solution for this problem. Traction basically involves using some kind of bracing to apply forces to the joints in your shoulders, hips, knees, etc. to pull apart or “distract” that joint just slightly – and release any compressive forces that are causing limited mobility (5).

For example, say you're a person who gets deep, aching hips when you finish a long run or up your running mileage. Sure, you can take a lacrosse ball to the side of your hips, or do a bunch of side-to-side dynamic leg swings, but you really want to get at the hip joint itself, you can do hip traction with a band (I personally use a Monster Band from Rogue Fitness) as an extremely effective way for helping to restore mobility to that hip joint – so you quit getting the hip joint pain altogether. You're basically “pulling apart” your hip socket. And boy, does it feel good.

To perform hip traction, you can get into an all-fours, crawling position with a long and straight spine, and then hook a giant elastic band high on the inside of your thigh, with the other end of the elastic band hooked to an immoveable object, like a bed post, couch, rack at the gym, etc. Move far enough away from that immoveable object so that you feel the band pulling tension on that hip. You then rock your butt side-to-side and front-to-back to move your hip in the newly opened space that the traction from the band has created. This movement under traction helps deliver small increases in lubricating fluid into the joint space and also to help to reduce any permanent cramps or spasms that have creeped into any overactive muscles surrounding that area of your hip.

I know this traction description can be tough to visualize, so for some video examples of what traction with a band actually looks like, check out any of the “rubber band” stretch variations in the mobility section of AllThingsGym.com. Many of these videos feature Kelly Starrett, the author of the aforementioned book “Becoming A Supple Leopard“. That book also includes detailed instructions on self-traction exercises.

Another traction tool that I keep around is an inversion table. You can get one of these bad boys for $100-300 on Amazon, or you could probably find on on Craiglist listed by somebody who bought one, never used it, and would practically pay you to take it away. After a long day of work on my feet, a long bike ride or a long run, I hang from my inversion table for 5-10 minutes. Not only does it apply potent traction to the knees, hips, neck and back, but it also does a great job helping to drain muscle and fluid from exercised tissue. And yes, you can do the cool upside-down sit-ups if you want extra inversion points.

Yep – that's about all you need for traction: an inversion table, a giant band, and a decent traction website or book.

Then you toss in a golf ball, the aforementioned foam roller, a lacrosse ball or series of lacrosse balls strung together like a Myorope, a rolling-pin like device like a MuscleTrac and the occasional tree stump, barbell, park bench or anything else you can rub up against in a legal way…

…and we can pretty much skip any extensive gear recommendation section because you'll have everything you'll ever need for mobility TLC.

———————————————

Food For Mobility

Of course, as you've probably come to expect by now, no section on the neglected training areas of an endurance training program would be complete without giving you some food and supplement tips. So it's time to put on my chef's hat and give you some kitchen and cupboard pointers for taking care of your joints and keeping your fascia nice and supple.

Bone Broth – Every week here in the Greenfield house, we make a big vat of bone broth that lasts all week long. Typically we use a whole chicken (although you can also use beef, pork or other bones). Once you’ve learned how to make it once, bone broth is easy to make over and over again, and is a fantastic source of vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and fatty acids. Not only can it make your entire body feel like a million bucks after you drink a cup, but when consumed along with the marrow that seeps into the broth, it can be one of the best things you'll ever do for your joints, joint pain and joint mobility. If you don’t have the time or desire to make bone broth, or you want to add even more joint healing compounds to a smoothie or shake, you can get some of the same benefits of bone broth by purchasing and using gelatin powder regularly. Gelatin powder is basically ground-up collagen, and you should use an organic, clean source such as Great Lakes or Bernard Jensen. If you really want to geek out on all the benefits of bone broth, check out the article “Why Bone Broth is Beautiful” (4). I'd recommend every endurance athlete in hard and heavy training drink a cup of bone broth every day to 2-3 days, and add 1-2 tablespoons of gelatin powder to smoothies.

Ginger – Ginger extract has been shown to be just as effective at reducing joint pain as ibuprofen, but is, of course, far more natural (1). You can simply slice up ginger, boil for 5-10 minutes, and eat 4-6 slices on any hard workout days. You can also toss a large chunk of boiled or raw ginger into a smoothie, or use grated ginger regularly in soups, stews, stir-fries or any other meals. I always have at least one big chunk of raw ginger root on the kitchen counter as a joint-supporting staple.

Ginger – Ginger extract has been shown to be just as effective at reducing joint pain as ibuprofen, but is, of course, far more natural (1). You can simply slice up ginger, boil for 5-10 minutes, and eat 4-6 slices on any hard workout days. You can also toss a large chunk of boiled or raw ginger into a smoothie, or use grated ginger regularly in soups, stews, stir-fries or any other meals. I always have at least one big chunk of raw ginger root on the kitchen counter as a joint-supporting staple.

Fish – Omega-3 fatty acids decrease the progression of osteoarthritis (15). Specifically, EPA and DHA inhibit the expression of various proteins that contribute to osteoarthritis, and decrease both the destruction and inflammatory aspects of cartilage cell metabolism. In a study in 293 adults without osteoarthritis, some with and some without joint pain, it was found that higher intakes of monounsaturated fatty acids or omega 6 polyunsaturated fatty acids were associated with an increased risk of bone marrow lesions, so shifting the diet toward foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids (like fish) while decreasing intake of omega-6 fatty acids (like vegetable oils, heated seeds and nuts, etc.) can be extremely helpful. Omega-3 fatty acids can help with stiff, tender or swollen joints and joint pain, and also help increase blood flood to joints during exercise.

So I recommend you eat several 6-8 ounce servings of cold-water fish weekly. Specifically, salmon, mackerel, trout, halibut, and white tuna each have more than 1,000 mg of fish oil, and a UK study found that regularly consuming this amount of fish oil is all it takes to stop cartilage-eating enzymes in their tracks (no mega-dosing required!). Of course, if you don't have time to fry a fish, you can also get omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil in a more concentrated capsule or liquid form, but be sure to use a cold processed, triglyceride-based form packaged with antioxidants such as Pharmax, Barleans, Carlson's or the SuperEssentials which I personally use and consider to be the best. Cod liver oil has also been shown to have great efficacy in supporting joint health (I'd recommend a fermented form of cod liver oil). I personally recommend 4g of fish oil or 1-2 tablespoons of cod liver oil consumed on any day for which you do not eat fish.

Antioxidants – The vitamins B and C increase cell wall elasticity and joint mobility, and can be found in just about any dark colored fruit, vegetable or starch. The inflammation-reducing polyphenols and bioactive compounds found in plants are no higher than in fruits such as blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, purple grapes, pomegranates and currants, vegetables such as purple cabbage, kale, organic tomatoes and dark orange carrots, and starches such as sweet potatoes, yams and taro. Any endurance athlete's refrigerator or countertop should be chock full of these colorful compounds to be used in salads, smoothies, juices and more.

——————————————–

Supplement Strategies For Increasing Mobility

Proteolytic Enzymes – As the name implies, proteolytic enzymes (also known as proteases) “lyse” or break down proteins. They include enzymes such as trypsin, chymotrypsin, papain and bromelain. You could, for example, pop a few enzymes before eating a steak to help digest the proteins that are in the meat. But when used outside of meals, proteolytic enzymes can accelerate a multitude of healing processes, because when not used for digestion in the small intestines, these enzymes are free to roam through your blood stream to break down hard protein, fibrin surfaces, scar tissue, granuloma, and tough cell coatings that can cause joint pain and lack of mobility (6). In Europe and Japan, proteolytic enzymes are used quite extensively to speed up healing from bodily injury or surgery (although in the USA and UK, they still fly under the radar).

Proteolytic Enzymes – As the name implies, proteolytic enzymes (also known as proteases) “lyse” or break down proteins. They include enzymes such as trypsin, chymotrypsin, papain and bromelain. You could, for example, pop a few enzymes before eating a steak to help digest the proteins that are in the meat. But when used outside of meals, proteolytic enzymes can accelerate a multitude of healing processes, because when not used for digestion in the small intestines, these enzymes are free to roam through your blood stream to break down hard protein, fibrin surfaces, scar tissue, granuloma, and tough cell coatings that can cause joint pain and lack of mobility (6). In Europe and Japan, proteolytic enzymes are used quite extensively to speed up healing from bodily injury or surgery (although in the USA and UK, they still fly under the radar).

You'll find some proteolytic enzymes in papaya, pineapple and meat, but for injuries and mobility, you'll need more concentrated sources (unless you feel like eating a wheelbarrow full of pineapples a day). Dosages vary, but if you're really struggling with fascial adhesions and lack-of-mobility due to previous injury or scar tissue, I personally recommend either Recoverease or Wobenzymes.

Glucosamine-Chondroitin – Glucosamine is an sugar present in the protective exoskeleton of shellfish, and chondroitin sulfate is a major component of cartilage. Glucosamine and chondroitin are also natural substances produced by your body. Glucosamine stimulates cartilage production in your joints and chondroitin helps to attract water to the tissue, which helps your cartilage stay elastic. Chondroitin may also block the action of enzymes that break down cartilage tissue (12). For this stuff to be effective at reducing joint pain or assisting with mobility, you need to look for a supplement that contains the “sulfate” form of glucosamine (glucosamine sulfate). The scientific evidence for this form is stronger than for supplements containing the glucosamine hydrochloride form. In addition, you need to use at least 1500mg of glucosamine sulfate per day, and you usually need to take it for three months or long to notice any improvement in stiffness, pain or mobility.

Myself and the athletes I coach have personally tried many different glucosamine-chondroitin blends and have settled on one called “Kion Flex” to be most effective. It's not an “everyday” supplement per se, but one to use if you really need improvements in mobility, you're injured, or you need to nip nagging joint pain in the bud. In addition to glucosamine-chondroitin, it contains a cocktail of anti-oxidants and anti-inflammatories such as cherry juice, ginger, turmeric, white willow bark, feverfew, valerian, acerola cherry, and lemon powder. Of course, it should go without saying that if you're vegan or have a shellfish allergy, this supplement wouldn't be the smartest idea.

——————————————–

Summary:

Here's the final word on mobility: when you begin to use the techniques you've just learned, you'll immediately notice changes in the way that you move, the way your joints feel and any nagging aches and pains.

But these changes will be absolutely minuscule compared to how you're going to feel and move in about 6 months to two years.

Why that specific time period?

Research on fascia (and the trusted word of Kelly Starrett) has shown that “rewiring” your fascia and completely changing your mobility and range-of-motion in a permanent and long-lasting way takes about 6-24 months.

So mobility is a game of patience.

And yes, it's totally worth it, even it means keeping a golf ball under your desk, a lacrosse ball in your underwear drawer, and a foam roller on your back porch for the next two years.

So what's next in “Beyond Training”?

In case you haven't been counting, there is one more essential element. of an endurance training program that most athletes neglect: balance. And trust me, balance goes way above and beyond standing on one foot while you're brushing your teeth.

Stay tuned for that next chapter in just one week – and remember, when this entire book is released in October, it's going to include a beautiful hard copy version for you to peruse at the beach or tuck under your arm to take to the gym, a nice budget-friendly paperback option, convenient Kindle format for you to stuff in an airplane carry-on, and for those of you who like to go old-school, an ancient Mesapotamian scroll format that is delivered to your doorstep in a giant dumptruck.

OK, maybe not the scroll part.

But isn't this whole thing cool? YOU get to witness the birthing of this entire manuscript, and when it's released, there are going to be tons of hidden bonuses that didn't appear in these blogged sections, including step-by-step training plans, videos, diagrams, hidden chapters that didn't make the final cut, and even live webinars with me for Q&A about everything in the book.

It's gonna absolutely rock, I'm stoked to have you as part of the journey, and yes, the book is still slated to be released this October. Spread the word by liking this post on Facebook, sharing it on Twitter, and if you're a Pinterest person, by doing whatever it is people do on Pinterest, which I believe is now legal in all 50 states. Oh yeah, and leave your comments below.

——————————————–

Links To Previous Chapters of “Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance, Health & Life”

Part 1 – Introduction

-Part 1 – Preface: Are Endurance Sports Unhealthy?

-Part 1 – Chapter 1: How I Went From Overtraining And Eating Bags Of 39 Cent Hamburgers To Detoxing My Body And Doing Sub-10 Hour Ironman Triathlons With Less Than 10 Hours Of Training Per Week.

-Part 1 – Chapter 2: A Tale Of Two Triathletes – Can Endurance Exercise Make You Age Faster?

Part 2 – Training

-Part 2 – Chapter 1: Everything You Need To Know About How Heart Rate Zones Work

-Part 2 – Chapter 2: The Two Best Ways To Build Endurance As Fast As Possible (Without Destroying Your Body) – Part 1

-Part 2 – Chapter 2: The Two Best Ways To Build Endurance As Fast As Possible (Without Destroying Your Body) – Part 2

-Part 2 – Chapter 3: Underground Training Tactics For Enhancing Endurance – Part 1

-Part 2 – Chapter 3: Underground Training Tactics For Enhancing Endurance – Part 2

-Part 2 – Chapter 4: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 1: Strength

-Part 2 – Chapter 4: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 2: Power & Speed

-Part 2 – Chapter 4: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 3: Mobility

-Part 2 – Chapter 4: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 4: Balance (coming soon!)

Coming in Part 3 – Recovery…

-Importance of when training adaptations actually occur (during the rest and recovery period) and show how to recover with lightning speed, including every beginner-to-advanced method such as ice, cold laser, PEMF, compression, electrostim, grounding, earthing, cold-hot contrast, ultrasound, etc…

-All about overtraining and exactly how to identify it, avoid it, and bounce back from it as quickly as possible, including a focus on self quantification methods such as heart rate variability and pulse oximetry, and biomarker testing for hormones, vitamins, minerals, etc…

-Beginner-to-advanced stress relief techniques, relaxation and sleep techniques for both home, as well as for traveling – including managing late nights, loss of sleep, napping, jetlag, etc.

-Advanced sleep-hacking methods using artificial light mitigation, binaural beats, etc…

-And much more!

————————————

References (more references coming soon):

1. Bliddal, H. (2000). A randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study of ginger extracts and ibuprofen in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 8(1), 9-12.

2. Borms, J. (1987). Optimal duration of static stretching exercises for improvement of coxo‐femoral flexibility. Journal of Sports Sciences, 5(1), 39-47.

3. Craib, M. (1996). The association between flexibility and running economy in sub-elite male distance runners. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 28(6), 737-43.

4. Daniel, K. (2003, June 18). Why bone broth is beautiful. Retrieved from http://www.westonaprice.org/food-features/why-broth-is-beautiful

5. Diab, A. (2013). The efficacy of lumbar extension traction for sagittal alignment in mechanical low back pain: A randomized trial. The Journal of Back Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, 26(2), 213-20.

6. Deitrick RE. Oral proteolytic enzymes in the treatment of athletic injuries: a double-blind study. Pa Med. 1965;68:35-37.

7. Earls, J. Myers, T. Fascial Release for Structural Balance. North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, CA, 2010.

8. Frey, L. (2008). Massage reduces pain perception and hyperalgesia in experimental muscle pain: a randomized, controlled trial. The Journal of Pain, 9(8), 714-21.

9. Gergley, J.C. Department of Kinesiology and Human Science, Stephen F. Austin State University. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2013 April;27(4):973-7.

10. Gleim, G. (1990). The influence of felxibility on the economy of walking and jogging. Journal of Orthoscopic Research, (8), 814-823.

11. Godges, J. (1989). The effects of two stretching procedures on hip range of motion and gait economy. Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy, (March), 350-57.

12. Hall, H. (2012). Effectiveness of glucosamine and chondroitin for osteoarthritis. American Family Physician, 86(11), 944, 998.

13. Herbert, R. (2002). Effects of stretching before and after exercising on muscle soreness and risk of injury: systematic review. BMJ, (March), 325-458.

14. Hubley, C. (1984). The effects of static stretching exercises and stationary cycling on range of motion at the hip joint. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 6(2), 104-109.

15. Hutchins-Wiese, H. (2013). The impact of supplemental n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and dietary antioxidants on physical performance in postmenopausal women. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 17(1), 76-80.

16. Jagomagi, G., & Juramiae, T. (2005). The influence of anthropometrical and flexibility parameters on the results of breaststroke swimming. Anthropol Anz, 63(2), 213-19.

17. Kyrolainen H, Komi P, Belli A. Changes in muscle activity patterns and kinetics with increasing running speed. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 1999, 13(4), 400-406.

18. Lowery, R. (2013). Effects of static stretching on 1 mile uphill run performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, (April)

19. Oagi, R. (2008). Effects of petrissage massage on fatigue and exercise performance following intensive cycle pedalling. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(10), 834-8.

20. Pasta G, Forsyth A, Merchan CR, Mortazavi SMJ, Silva M, Mulder K, Mancuso E, Perfetto O, Heim M, Caviglia H, Solimeno L. Orthopaedic Management of Hemophilic Arthropathy of the Ankle. Haemophilia, 14 (Suppl. 3):170-176, 2008.

21. Sayers, A.L., Farley, R.S., Fuller, D.K., et al. Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2008 Sep;22(5):1416-21.

22. Simic, L., Sarabon, N., Markovic, G. Motor Control and Human Performance Laboratory, University of Zagreb. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2013 Mar;23(2): 131-48.

23. Zourdos, M. (2012). Effects of dynamic stretching on energy cost and running endurance performance in trained male runners. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(2), 335-41.

24. Silva, A. (2007). The use of neural network technology to model swimming performance. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 6(1), 117-125.

Furthermore, please discuss with the practitioner areas in places you accumulate probably the most muscle tension and stress.

Here are a couple of general guidelines to follow

along with when researching an ideal Massage Chair to fit your needs:Basic

Comfort and Looks – Take some time to truly sit within the Chair

and acquire a perception of your own ease and comfort in that model.

Nowadays, this kind of natural health care has used not merely to the treatment and prevention of sickness and disease and also as a way to stay fit and having a great day with the luxurious way of relieving stress.

Hey Ben, how you heard of Eldoa? My trainer/PT has had me use that to work on my bad back, and it seems to be helping with my mobility. I'd be curious about your opinions or thoughts.

Greetings Ben,

This chapter totally hits home with a problem I've been dealing with over the last 2 years. In short, I got into long-course triathlon way to soon and with bad form. My hip mobility sucks, but is improving. The result was a chronic tightness that built-up where the (left) psoas muscle meets the spine. This caused poor motor control in my hips, lifting my left leg fully, left glute not firing complete, and a loss in ground contact in my left foot (near the inner heel.)

Improvements have been very slow, but "Becoming a Supple Leopard" (a book you recommend not long ago) has offered great insights. I practice all that you've been preaching, but still feel I am plateauing with my efforts.

My question is do you see the psoas muscles as a common problem area in triathletes? And can you suggest any specific stretches or smashes that will help release psoas muscles tightness?

Thanks for being a wealth of knowledge.

Cheers,

Tyler

Yes, I specifically roll "back and forth" on the foam roller up in the psoas area, and then follow that up with a lunging hip flexor stretch. In Kelly's book, everything you see in the anterior hip mobility section helps too!

Thanks for the great reading Ben. In the section on food under antioxidants the following sentence is written:

“The inflammation-reducing polyphenols and bioactive compounds found in plants are no higher than in fruits such as blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, purple grapes, pomegranates and currants, vegetables such as purple cabbage, kale, organic tomatoes and dark orange carrots, and starches such as sweet potatoes, yams and taro.”

This sentence is the first mention of ‘plants’ but talks as if they have already been spoken about or are assumed knowledge. Just thought it may read a bit clearer if this is clarified.

Hey Ben, I'm wondering if you can use a foam roller incorrectly? I have somehow developed really tight hip muscles, starting in my low back that goes through the butt, the hip and now is starting to travel down my leg (right side only). I was using a foam roller consistently for over month, but it only seemed to get worse. I have since stopped, and it's still quite painful. Could I have only made it worse from poor form on the foam rolling?

Yep, here's an example of all the "wrong" ways to use a foam roller: http://b-reddy.org/2013/05/20/issues-with-foam-ro…

Yikes, after reading that article it sounds like no one should foam roll ever!

Like Terri above I'm also an older runner/biker (52 year old) that really enjoys your blogs. I find your articles very informative and useful, especially the chapter on mobility…the foam roller is excellent for finding problem spots!! Let us know when your book is finished I'm looking forward to reading it.

Hope you enjoy the Memorial Holiday weekend!

Cool stuff as usual! I'm wondering, though, about using the linked study as an argument for the ginger extract since the study concludes that "…a statistically significant effect of ginger extract could only be demonstrated by explorative statistical methods in the first period of treatment before cross-over, while a significant difference was not observed in the study as a whole.".

There are lots of other studies on ginger coming in the reference section soon.

Hi Ben,

I could just be my set up (?), but the link for:

‘-Part 2 – Chapter 3: Underground Training Tactics For Enhancing Endurance – Part 2’

just keeps going to Part 1 in all the links, on all the pages I can get to, that reference it.

I could only find the page (Part 2) by going through the ‘RSS’ link history.

Great info. Thank you.

Colin

Germany

Thanks, will look into this ASAP!

Hi Ben

thx for a great article! A note about rolfing. Dr Ida Rolf(female) created the work and its way more that facial adhesion release. The 10 series reorganizes the whole body in gravity. The practitioners study/evaluate how each client moves and basis treatment on those restrictions. The focus is not on symptoms but in getting the body back in alignment thus movement is greatly improved. The symptoms generally go away once the strain patterns are removed.

Thanks for clearing that up, Lucia!

Hey Ben, I love reading your stuff. I am in my fourth year of triathlon training, starting at age 52. I am doing my first half iron in Kona next month. My training has been supported by the AIDS foundation T2EA program and I spend time reading about triathlons from your stuff and a variety of other sources. For the half iron, I’ve had to cobble together my own training program, hard to do…AIDS foundation was supporting it but they backed out and I was left with either not doing it and losing my entry fee or boldly going forward and making the attempt by planning my own training. I used your videos to learn how to pack transition bags and I read your entries with interest. You are quite a bit younger and in better shape than me so some of your stuff is less relevant than it might be. Maybe you need a chapter on older triathletes?

Anyway, I wanted to say that you should talk about the mental aspect of training as well as the mental (visualization) effects of stretching and training. years ago I discovered visualization through tae kwon do and after a serious back injury the effects of visualizing the effects of my efforts to heal. Going deep inside yourself to understand the effects of what you are doing on your body at a cellular level does have an impact. I read at one time about a young boy that was cured of cancer during his treatments who had visualized his cancer cells being killed by the treatments like a video game. If you have never tried to “feel” your blood pumping in your body or been still enough to feel your cells altering, you might not know how well this works, but you strike me as the kind of guy you might have tried this already. Good luck on your book.

Terri, all of this stuff is extremely relevant to older athletes! In the finished book, I will also have some sidebar sections for that as well. Thanks for the tips on visualization.

Thanks again for another great chapter and allowing us to go on this book journey with you. Just a quick typo correction-“For example, if you’re genetically prone to hypermobility, too much stretching can make also make you – drumroll please – too stretchy.”

Looks like you’ve got an extra “make” in there.

Thanks for the keen eye Mark! I'll get this fixed ASAP!