April 20, 2013

Welcome to Chapter 4 of Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance Health & Life.

In this chapter, you're going to learn the real reason why 99% of endurance athletes move inefficiently, get injured and stay injured and constantly fight a frustrating and never-ending battle against their own bodies.

You're also going to learn solution to the frustration of getting injured all the time, hitting that glass ceiling of performance potential or constantly getting stuck in a rut. The solution can be found within the five essential elements of an endurance training program that most people neglect.

It's actually quite rare to meet a triathlete, marathoner, cyclist or swimmer who truly includes each of the elements you're about to learn in their weekly routine. But if you personally learn and begin to implement each of these five elements, you're going to find that your body stays put together, you get injured less, you bounce back from your workouts faster, and you move with more grace and ease.

So let's jump into each of these five elements, and as usual, leave your questions, comments, feedback and edits below this post. In Part 1 of this chapter, we're going to focus on strength, in Part 2 of this chapter Power and Speed, and in Part 3 Balance and Mobility.

By the way, the audios, videos, slides and take-away notes from the recent, absolutely epic, “Become Superhuman” live event are all available for instant download, including fantastic presentations by Dave Asprey, Nora Gedgaudas, Phil Maffetone, Ray Cronise, Monica Reinagel and more… Get lifetime access by clicking here.

—————————————–

Why The Essential Elements Make Sense

If you look at the training methods of best athletes and teams on the face of the planet, you'll notice that they spend what seems to be an inordinate amount of time doing something other than their actual sport.

Take an NFL football player, for example.

During a four month internship at Duke University, I worked with the Kansas City Chiefs on training and rehab of some of their standout offensive linemen. On any given day, these players would spend an hour in the weight room, 30-45 minutes performing mobility drills, 20-30 minutes engaged in recovery protocols, and then 2-3 additional hours of actual practice.

Or look at an elite swimmer. In one interview, swimmer Dara Torres described her day as follows:

“…when I’m home in Florida I get up at about 6:45 and walk my dog. Then I get my 5-year-old daughter up and feed her, then head off to practice. I start swimming at 8. I’ll swim anywhere from an hour to an hour and 45 minutes. Then I’ll do some weights and sometimes resistance work for a while followed by lunch. After that I do about two hours of Ki-Hara Stretching…” (8).

In a build-up to the 2012 Olympics, the Huffington Post interviewed U.S. Olympic Committee Strength and Conditioning Coach Rob Schwartz, who trains many of the athletes on Team USA, and when asked about a typical day in the life of any Olympian, here's what Rob had to say:

“A typical day for our athletes starts fairly early with breakfast between 6 and 7:15 a.m., as their first training or practice is at 7 or 8 a.m. It depends on the sport, but most practices are two hours per session and there are two sessions per day, five to six days per week. Their strength and conditioning session is usually one to one-and-a-half hours, with three to four sessions per week. The athletes also get “extra workouts,” which are anywhere from 15 to 45 minutes, and focus on their individual needs, whether it’s extra work in the weightroom or addressing a sport skill. Then they have sessions with sports medicine for rehab or recovery work. We spend a lot of time teaching the athletes that recovery doesn’t just happen, they have to work at it. Proper nutrition/hydration and quality sleep have to come first and can’t be overlooked. They have to make time for contrast baths, sauna, compression work with the Normatec system and massage…”(7).

Perhaps right now you're chuckling. After all, most of us are not Olympic athletes prepared to devote our lives to training, eating and recovering. We have to squeeze in work, meal preparation, chauffeuring kids, mowing the lawn and doing everything else that life throws at the average endurance athlete. By the time we swim, bike or run, is there really time left over for all this other stuff?

And let's face it: to a true endurance junkie it's simply not glamorous or enticing to balance on one leg while lifting a heavy object overhead, learn how to properly perform a lateral lunge, or figure out what the heck a plyometric is.

To the first point, my advice is to simply keep reading, because I'm going to teach you how to easily implement each of the five essential elements into your life and workouts without becoming a gym rat or chaining yourself to a foam roller.

And to the second point, the unfortunate reality is that the line of thinking that keeps you only swimming, only biking or only running is the same line of thinking as someone who:

-drives a car (or bicycle) into the ground and never maintains their vehicle with anything even so slight as an oil change, then throws up their hands in despair when the engine starts smoking…

-never visits the doctor, pays attention to their health, or does any preventive tests, then gets frustrated and confused when they get sick or have to shell out money for an emergency doctor's visit…

-expects their home appliances like the washer, the dryer, the stovetop, the oven or the dishwasher to simply always work with zero maintenance, and then is forced to spend an entire paycheck on an expensive repair…

You get the idea.

When it comes to training for endurance, it's very easy to instead get caught up in an endless cycle of swimming, biking, running, rowing, hiking, and a host of other “chronic repetitive motion” activities, while neglecting the stuff that actually keeps our bodies able to do what we love. So while you don't need to spend all your precious hours hoisting a barbell or jumping onto a box, you simply can't be a complete slack-off when it comes preparing your body adequately for pounding the pavement or hammering the pedals.

Fair enough?

So now let's jump into the first of the five essential elements: strength.

—————————————–

Essential Element 1: Strength

Strength is defined as the ability of your musculoskeletal system to generate high amounts of force.

Or put more simply, strength is the ability of your muscles to move stuff.

That stuff might be a barbell that you're moving through heavy squat, or a bicycle that you're moving 140.6 miles, or your own body that you're moving 26.2 miles. Regardless of the resistance, it takes a certain amount of muscle to move that stuff. In the last two chapters, you learned about a host of reasons why weight training is important, but strength is certainly one of the major benefits.

Want an example of how lack of strength can hold you back?

Look at a Kenyan marathoner. There's a reason you simply don't see these guys or girls dominating a sport like Ironman triathlon. Despite their aerobic superiority, they simply don't have the leg muscle strength to generate the power necessary to move a bicycle 140.6 miles. For this same reason, you tend to see professional Ironman triathletes be slightly more muscular than their relatively slight, shorter distance distance counterparts, as you can see from the photos below.

If you're a triathlete, and you tend to be a relatively strong runner, but weak on the bicycle, a lack of muscle and strength may also be an issue for you.

So how much strength or muscle do you actually need for endurance sports?

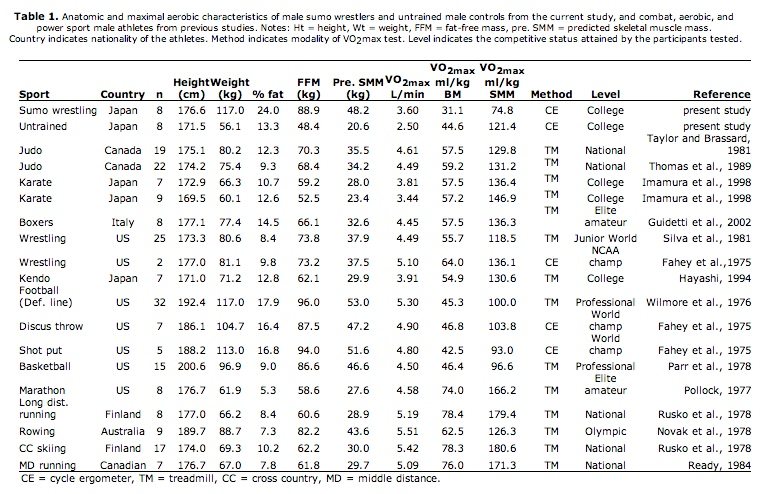

Fortunately, this has been studied by researchers (2) who looked at aerobic capacity (VO2) per kilogram of muscle mass in a group of individuals ranging from endurance athletes (marathon runners, cross-country skiers, rowers, etc.) to power athletes (shot putters, football players, sumo wrestlers, etc.). In the endurance athletes, it was found that aerobic capacity peaks out at approximately 180 milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of appendicular (arm and leg) muscle mass. Based on the data from the study, there appears to be a “ceiling” at which increases in muscle mass do not result in additional increases in VO2max.

The table below shows the findings of that study (click on table to magnify):

Take a marathoner, for example, who you can see from the table has a VO2max of 4.58 liters of oxygen per minute. If that marathoner wanted the maximum amount of muscle to get the highest possible strength without sacrificing endurance, they'd want about 27.6 kilograms predicted skeletal muscle mass (pre-SMM).

Now I'm certainly not proposing that you rush out to find a fancy body fat scale which allows you to measure your body fat and lean muscle mass so that you can get the exact amount of muscle necessary for ultimate success in endurance sports. But what I am proposing is that you not completely neglect the essential element of strength if you are serious about everything from endurance performance to health to longevity to (if this is important for you) looking good in a t-shirt and fitted jeans.

—————————————–

Muscle Is Not Just Bulk

Some would argue that muscle is just extra bulk.

It's certainly true that it is not necessary for an endurance athlete to build rippling muscles capable of producing enormous amounts of force. Since muscle takes significant amounts of energy to cool and carry, there is without doubt a point of diminishing returns as an aerobic athlete builds muscle. Those diminishing returns were approximated in the table above.

I personally experienced the disadvantage of muscle bulk when began the sport of triathlon from the sport of bodybuilding, and some of my most painful memories of endurance competition come from the soreness, dehydration, overheating and overall discomfort associated with carrying over 25 pounds of “extra” show muscle.

But muscle mass is not necessarily synonymous with strength.

The reason for this lies in the relationship between the nerves, the muscle and something called the motor unit. A motor unit is defined as a nerve and all the muscle fibers stimulated by that nerve. Muscle fibers are grouped together as motor units. If the signal from a nerve is too weak to stimulate the motor unit, then none of the muscle fibers in that motor unit will contract. But if signal is strong enough, then all of the muscle fibers in the motor unit will contract. This is called the “all-or-none” principle (1).

It doesn’t take much of a signal to recruit slow-twitch, or endurance muscle fibers in a motor unit. It takes a stronger signal to recruit fast-twitch, or explosive muscle fibers. However, the goal of weight training and strength building is not to increase the signal to the fibers, but rather to train the body to be able to recruit multiple motor units, whether those motor units are comprised of slow-twitch or fast-twitch muscle fibers (9). The strongest athletes in any sport have the capability to recruit multiple motor units, which means more fibers are firing, which increases force production and strength.

So as an endurance athlete, you can have a relatively small number of motor units, but with proper training, can gain the ability to recruit a significant number of those motor units simultaneously. If this is the case, you don’t need much muscle, but just the ability to be able to wholly recruit the muscles that you do have.

Of course, recruitment of multiple motor units is not the only benefit of strength training. Over 20 years of research have successfully demonstrated lower injury rates for the shoulders, knees, hamstrings, low back and ankles in athletes including swimmers, cyclists and runners when strength training was used to strength the soft tissue surrounding and supporting the joints (16). In some cases, injury prevention is due to correction of a muscular imbalance through the use of targeted weight training, and in other cases, injury prevention is due to the increased ability of a joint to absorb impact (one reason why the Ironman triathletes described earlier tend to be “bulkier” than their shorter distance counterparts).

Finally, the hormonal response to strength training is significantly different than the response to endurance exercise. From the perspective of an endurance athlete, an increase in anabolic hormones such as testosterone may be beneficial for decreasing body fat, improving mood, having a better sex life, or increasing longevity. Studies have shown that endurance trained men tend to have lower levels of testosterone, compared to both sedentary and resistance trained men. A 2003 study entitled “Effect of Training Status and Exercise Mode on Endogenous Steroid Hormones in Males” (20) discovered that compared to an endurance training group and sedentary group, the resistance training group had higher levels of luteinizing hormone, DHEA, cortisol, total and free testosterone and hematocrit.

Finally, the hormonal response to strength training is significantly different than the response to endurance exercise. From the perspective of an endurance athlete, an increase in anabolic hormones such as testosterone may be beneficial for decreasing body fat, improving mood, having a better sex life, or increasing longevity. Studies have shown that endurance trained men tend to have lower levels of testosterone, compared to both sedentary and resistance trained men. A 2003 study entitled “Effect of Training Status and Exercise Mode on Endogenous Steroid Hormones in Males” (20) discovered that compared to an endurance training group and sedentary group, the resistance training group had higher levels of luteinizing hormone, DHEA, cortisol, total and free testosterone and hematocrit.

The take-away message for endurance athletes is that a focus on pure aerobic training with no strength training may result in a less-than-ideal hormonal response to exercise, which may affect reproductive function, drive, and physical appearance.

So let's look at the exact sets/reps/rest and strategies necessary to build strength – and if you want an entire book devoted to this subject (written by yours truly), check out “The Ultimate Guide To Weight Training for Triathletes“, which is applicable to athletes in any endurance sport and delves much deeper into the research behind the benefits of strength training.

—————————————–

Training Strategies for Increasing Strength

There are three primary strategies you should use for increasing strength: multi-joint exercises, periodization, and proper timing. Here is an overview of each.

Strength Strategy #1: Use Large, Multi-Joint Exercises

Strength training experts and triathlon coaches always seem to be highlighting the injury-preventive and performance importance of tending to small, supportive muscles that are notoriously weak in endurance athletes, such as the shoulder’s rotator cuff, the outer butt’s gluteus medius, the small scapula muscles along the shoulder blades, and the abdominal, hip and low back region, or “core” (15).

Don't get me wrong: these certainly are weak areas that shouldn't be neglected. But for the average working, time-crunched endurance athlete, it simply doesn’t make sense to devote several extra hours per week performing isolation exercises for these tiny, supportive muscles.

For example, a common exercise for the rotator cuff involves multiple sets and high repetitions of internal and external rotation with a piece of elastic tubing. If you have 30 minutes at the gym over lunch hour, do you really want to spend 10 minutes of that time standing relatively motionless, as a few small muscles in your arm and shoulder are firing?

Instead you’ll find your limited time better suited to large, multi-joint movements that incorporate the rotator cuff, but also use many of the other major muscles of your body, thus training coordination, motor-unit recruitment, and muscle strength (18), while also strengthening the rotator cuff. Two examples in this case would be barbell or dumbbell overhead press, and bodyweight or assisted pull-ups, both of which involve multiple large muscles and full upper body coordination, but also incorporate the smaller, stabilizing muscles of the rotator cuff.

Other examples of good full body or multi-joint movements include squats, cleans, overhead presses and deadlifts. Watch the video below to see me demonstrate 4 key moves that each incorporate multiple joints.

Strength Strategy #2: Periodize

In the same way that you should't do the same swim, bike and run workouts all year long, if you use the same strength training volume and intensity, and the same sets, weight and the number of repetitions all year long, you’ll experience burnout and decreased performance. So just as you should make slight alterations or major changes to your swimming, cycling, and running routine, you should also modify your weight training routine as the time of year changes (10).

For example, if you decrease sets, increase power, and incorporate more explosiveness as your high priority races draw near, you can allow your strength trained muscles to achieve peak performance on race day.

This strength and performance peak is achieved through “periodization”. Periodization is the scientific term for splitting a training year into periods and focusing on a specific fitness goal for each period. Most swim, cycle and run programs use periodization, and by following the simple rules below, you’ll be able to effectively periodize your strength training.

- Off-Season: If your goal is to develop muscle mass, tone muscle in a specific body area or part, or build significantly greater strength, this is the time to do it. Traditionally, the off-season is a time of year when there are few or no races, and you're often engaged in other cross-training activities that go beyond swimming, cycling or running. Off-season strength training workouts are performed in a set and repetition range designed for muscular growth (hypertrophy) and because endurance is de-emphasized, it is not as important during strength training to reduce overly fatiguing a muscle or producing soreness – instead, these effects are often necessary to achieve significant growth in muscle mass or strength. I call this off-season strength training phase the “Muscular Enhancement” phase, and it generally consists of 3-5 sets for each exercise, with 10-15 reps, 65-75% intensity, 30-60 seconds rest between sets, or circuits with minimal rest.

- Base/Foundation: An endurance athlete's strength training goal during the base or foundation part of the season (which typically follows the off-season) should be to develop strength and muscular coordination, while considering the added focus that will be placed on sport specific training, and the need for decreased soreness. Most endurance training programs incorporate high amounts of training volume during base training, so the number of strength training workouts will naturally decrease. Plyometrics and very explosive training should yet be introduced, as explosive forms of training do indeed increase risk of injury. Most workouts will include 3-4 sets of 8-10 reps, with a heaver weight than used in the off-season, and the goal of completing 1-2 weight training sessions each week. I call the base training for strength the “Foundation Strength” phase, and recommend 3-5 sets of 8-10 reps at 75-85% intensity with 60-90 seconds rest.

- Build: The build period of an endurance training season typically increases in both the intensity and the volume of endurance training. While it may seem logical to simultaneously increase intensity and volume of strength training, this can detract from endurance sessions and increase risk of overtraining. Instead, like base training, strength training frequency should be maintained at 1-2 sessions each week, but with the time flexibility to lift as infrequently as once per week. I call this the

“Progressive Strength” phase, and it typically consists of 2-4 sets of 6-8 reps at 85-95% intensity, with 90 seconds to 2 minutes rest. Typically at this point in the season, I'll also begin to include a plyometric component – either performed separately or at the same time as the weight training session.

- Peak and Taper: While strength and increased recruitment of muscle motor units can be built and maintained during off-season, build and base periods, the goal (during the 2-4 peak and taper period before a race) is simply to maintain neuromuscular coordination and peak power. When these strength training sessions are performed properly, there will be little to no soreness or muscle failure, but a high amount of muscle fiber stimulation. All lifts should be performed explosively, in most cases with a lighter weight than used in previous periods. I call this the “Peak Phase” and recommend just 1-3 sets of 4-6 reps at relatively light weight of 40-60% intensity lifted quickly, and a strength training frequency of 1-2 sessions each week.

- Race: While it is acceptable to perform strength training for up to 72 hours prior to your low priority races, for mid-to-high priority races, no strength training is necessary during race week, since it can really tear up your muscles. If several high priority races are being performed on consecutive weeks, and weight training, strength and power maintenance are a desired component of those race weeks, then a single weight training session can be performed at least 72 hours after a race and no more than 72 hours prior to the next race. The same set, repetitions, load should be used as during the peak and taper period – and occasionally simple body weight training methods can be used to reduce joint load.

In case you didn't notice, this advice contradicts the typical endurance athlete strength-training advice to simply devote the off-season to strength training, and then completely back off the heavy lifting and do basic core, body weight and stability exercises during the entire race season. Considering it takes just seven days to begin to lose significant amounts of muscle and strength, this strategy is a surefire way to lose the benefits of all your hard work.

This is especially true if you're a longer course endurance athlete such as an Ironman or ultrarunner. In these longer events, the closer you get towards the end of the day, the less important your cardiovascular fitness becomes and the more important your sheer strength and ability to hold your body together until the finish line becomes. Ignoring strength training during the base or build periods leading up to your event allows you to avoid losing the strength you gain over the off-season.

Strength Strategy #3: Use Proper Timing

Now that you have a basic idea of the yearly overview of strength training for endurance athletes, it will be important to understand how to integrate strength training into a typical week of endurance training, and there are three basic timing rules to follow as you set up your week:

- Timing Rule #1: Prioritize endurance training such as swim, bike and run workouts. If you’re pressed for time, you simply must train as specifically as possible. Therefore, if your day calls for a swim, bike or run session and a strength training session, perform the swim, bike or run session first, followed by the strength training session, either immediately after, or later in the day (14). There are additional benefits to this rule. The first benefit is that you will engage in better biomechanics because your muscles will not be pre-fatigued or broken down by strength training. The second is benefit is that research has shown a higher calorie-burning response when strength training is preceded by cardio, rather than vice versa. The only exception to this rule is the occasional need to train in a pre-fatigued state, in which case a short, tempo swim, bike or run session could be performed immediately after a strength training session.

- Timing Rule #2: Space strength training workouts that target the same muscle groups by at least 48 hours (12). Muscles will take at least 48 hours to recover between strength training sessions, so if, for example, a session includes barbell squats, and a subsequent weight training session includes dumbbell lunges, then space these sessions by at least 48 hours since they train similar muscle groups. This is only necessary if the workouts actually contain exercises that target the same muscle group. Otherwise, you can do strength training for different muscle groups on consecutive days.

- Timing Rule #3: Perform short and frequent or long and infrequent strength training workouts. In an a frequent scenario, two to three 20-45 minute weight training workouts can be performed on a weekly basis (3). In an infrequent scenario, a single, 50-70 minute full body strength training session can be performed on a weekly basis. There is absolutely no need to for an endurance athlete to strength train more than three days per week, especially if you're following the Ancestral Athlete rules of performing HIIT and Greasing the Groove. But if you're weak and need to build strength, I recommend you incorporate three strength training sessions per week, and then 1-2 sessions per week for continued maintenance.

—————————————–

Sample Strength Training Scenarios

The table below gives you some workout scenario options based on the number of days per week that you have available to strength train, along with the type of workouts you might choose. It is assumed that each of the workout scenarios above will organically work in not just strength, but also power, speed, balance and mobility, which you'll learn about in the other parts of this chapter.

Weight Training Frequency/Mode Table*

| Frequency | 1x/week | 2x/week | 3x/week |

| Option 1 | Session 1: Full Body | Session 1: Upper BodySession 2: Lower Body | Session 1: Upper BodySession 2: Lower BodySession 3: Weak Area/Trouble Spots |

| Option 2 | Session 1: Pushing exercisesSession 2: Pulling exercises | Session 1: Full BodySession 2: Core + Weak Area/Trouble SpotsSession 3: Full Body | |

| Option 3 | Session 1: Full BodySession 2: Full Body | Session 1: Core + Weak Area/Trouble SpotsSession 2: Full BodySession 3: Core + Weak Area/Trouble Spots | |

| Option 4 | Session 1: Upper and Lower BodySession 2: Core + Weak Areas/Trouble Spots | Session 1: Full BodySession 2: Full BodySession 3: Full Body |

These are just samples of ways that you can work in strength, but the training plan that you'll get access to as part of this book will incorporate these type of strength sessions and strategies (along with the isometric training you learned about in the underground training tactics chapter).

—————————————–

Foods For Strength

In Part 4 of this book, you'll get full diet scenarios for both vegans and omnivores, but as we progress through each of the five essential elements of endurance training, I'll be giving you some basic nutrition and supplement pointers that focus on those specific strategies, so in this section you'll get some basic food strategies for strength.

-Eat a Testosterone Supporting Diet

A testosterone supporting diet includes adequate amounts of zinc, cholesterol, B vitamins, and arachidonic acid (4). You get these type of compounds by including foods such as grass fed beef, oysters, eggs, garlic, cold water fish, and broccoli. We'll get more into testosterone support in both the recovery and the supplements chapter.

-Avoid Excessive Calorie Restriction, Excessive Alcohol, Soy & Caffeine

Each of the four components listed above can put a huge dent in your ability to build strength or add muscle (13). In addition to being careful with alcohol (more than 1 drink per day), soy (especially unfermented soy sources like tofu, soy milk, soy nuts, etc.), and caffeine (more than 1 cup of coffee per day), you should pay attention to the protein intake scenarios you'll learn in a bit, and eat at least as many calories as are necessary to sustain your metabolism, which you'll learn more about in the nutrition chapter. And if your goal is to actually build significant amounts muscle, you need to eat 500-1000 calories over and above your basic metabolic needs!

-Keep Blood Amino Acids & Glycogen Levels Topped Off

For building strength as quickly as possibly, you should have high levels of blood amino acids and storage carbohydrate levels when you hit the weights (17). The best way to achieve this is by avoiding fasted strength training sessions, spreading 20-25g protein portions throughout day with a focus on focusing on highly bioavailable proteins such as goat-based proteins or vegan based proteins without added sweeteners, soy, corn, etc., use of essential amino acids prior to or during strength training, and timing of your biggest carbohydrate intake prior to your strength training sessions.

—————————————–

How Much Protein Do You Need?

I realize that I just emphasized that you should get adequate protein for strength building, but generally, the importance of a high total volume of protein is blown way out of proportion – to the detriment of your liver and kidneys.

Sure, you certainly need the stuff. After all, when you eat protein, it gets broken down into protein building blocks called amino acids, and the amino acids are used for everything from cellular repair of all your damaged muscle fibers to a host of other metabolic reactions (19).

So to determine how much protein you actually should be getting, you need to be familiar with a term called “nitrogen balance”.

Here’s how nitrogen balance works:

Nitrogen enters your body when you consume protein from food or amino acid supplements, and nitrogen exits your body in your urine as ammonia, urea, and uric acid (all the breakdown products of protein) When the amount of protein you eat matches the amount of you use, you’re in nitrogen balance.

As you can probably deduce, if you don’t eat enough protein, you’ll be in negative nitrogen balance and quite unlikely to be able to repair muscle after a workout (a “catabolic” state), and if you consume too much protein, you’ll be in positive nitrogen balance, and while you’ll have what you need for muscle repair (an “anabolic” state), there can be some health issues that arise when you achieve too positive a state of nitrogen balance – since all that ammonia, urea and uric acid has side-effects (we’ll get into that in just a bit).

The current US recommended dietary allowance (RDA) is 0.36 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day (0.8g/kg), and was designed for most people to be in nitrogen balance – without protein deficits or protein excess. While athletes and frequently exercising individuals need more protein than this, you’ll frequently see bodybuilders, football players, weightlifters and other big strength and power athletes taking this to the extreme and consuming far in excess of this protein RDA (in some cases up to 2 grams per pound!)

But studies such as this one suggests that even for athletes, there really isn’t much additional benefit of exceeding 0.55 grams per pound of protein (1.2g/kg) if you want to maintain nitrogen balance (11). If you’re trying to exceed nitrogen balance for the purpose of putting on muscle, this study indicates that you don’t need to eat more than 25% above that 0.54 g/lb, which would be 0.55×1.25, which is 0.68 g/lb, or 1.5g/kg (22).

A spinach salad with fresh vegetables, hummus or flax seed crackers, and sardines is a common lunch for me, and has about 30g protein.

So let’s put those numbers into context. I weigh 175 pounds. If I don’t want to gain muscle, and I just want to make sure I’m getting enough protein for muscle recovery and body repair, I should eat 0.55×175, or 96 grams of protein.

Rounded up to a nice even number of 100 grams, that means I could have a couple scoops of an organic whey or vegan protein powder with my morning breakfast (which I do), a can of sardines over my salad at lunch, and 4-6oz of chicken with dinner. That’s easily 100 grams, and doesn’t even count the other protein I get from seeds, nuts, grains, legumes, etc.

And if I wanted to gain muscle, I could eat 0.68×175, or about 120 grams. So I would basically just add in a couple handfuls of almonds and a dollop of yogurt and I’d be good to go.

So what are the risks of eating excess protein, or having your nitrogen balance too great?

First, consider that ammonia is a toxic compound to the body. Once you get close to about 1000 calories a day of protein (that’s about 250 grams), you can longer convert ammonia to urea, and you begin to build up this toxin within your body. This is extremely stressful on your internal organs, especially your kidneys (21).

Next, excess protein can cause dehydration if you do not drink enough water. This is because your kidneys need more water to convert ammonia into urea.

Most interestingly to me, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a gene in your body that is directly correlated to accelerated aging. Decreased activity in this gene is directly correlated to caloric restrictions and lower amino acid intake (6). So excessive protein intake and a constantly positive nitrogen balance could actually shorten your life!

Take-away message: eat as much protein as your body needs for repair and recovery, eat a little more if you want to put on muscle, and then take in the rest of your calories from healthy fats and vegetables, with limited fruits and carbohydrates for fueling intense bouts of physical activity.

—————————————–

Supplements For Strength

The following are my top recommended supplements for building strength as quickly as possible (5). We'll cover more of the nitty-gritty science in the supplements section of this book, but for now, here are my basic recommendations:

-20-25g portions of DEEP30 protein (whey) or LivingProtein (vegan) spread throughout day, at 0.7-0.8 grams per pound body weight. See reasoning above!

–Creatine – 0.3g/kg bodyweight for 5-7 days followed by 5g/day. As you already learned earlier in this book, creatine's main action in the body is to store high-energy phosphate groups in the form of phosphocreatine. During strength training sets, phosphocreatine releases this energy to aid muscle contraction. This mechanism of action is what causes creatine to increase strength, but creatine can also benefit nearly every body system, including your brain, bones, muscles, and liver. Despite popular belief, no need to cycle on and off creatine.

–Carnitine – 750mg-2,000mg/day – in 2 doses. Carnitine has been shown to be very effective in alleviating the side-effects of aging, such as neurological decline and chronic fatigue, and also improving insulin sensitivity and blood vessel health. It has beneficial effects on neurons, repairing them from damage induced by some states such as high blood sugar, and can also be used as a brain booster due to its effects at increasing alertness, mitochondrial capacity, and neuron activity. It also increases fat burning and mitochondrial respiration. So you get a brain buzz, along with more energy when you use the stuff prior to strength training. Good brands vary.

–Citrulline – 6-8g, 30-60 minutes before exercise. The mechanism by which citrulline exerts its benefits is by aiding in ammonia detoxification. Ammonia is a byproduct from muscle metabolism during exercise (from use of ATP) and when it builds up it can cause less calcium release and declining pH in muscles, thus lower muscle contraction capability. So citrulline lowers ammonia. It also increases ATP and phosphocreatine replenishment rates during workouts and delays time to exhaustion during weight training sets. Recommend Citruvol.

–Beta-Alanine – 2-5g, 30-60 minutes before exercise. Beta-Alanine is a modified version of the amino acid alanine, and when ingested, it turns into the molecule carnosine which acts as a potent acid buffer in your body. Carnosine is stored in your cells and released in response to drops in pH (increases in acidity . Increasing your stores of carnosine can protect against diet induced drops in pH (such as can occur from ketone production in a low carbohydrate diet) and from exercise induced lactic acid production. By buffering lactic acid, beta-alanine can enhance strength performance, and many people note being able to perform one or two additional strength reps when popping this stuff.

–Essential Amino Acids – 5-10g before and then every 60-90 minutes during exercise. I have a very comprehensive article on the benefits of essential amino acids which you can read here, and I highly recommend the brand MAP.

-Daily serving of concentrated greens (to balance pH). Recommend Enerprime (capsule), Capragreens (low calorie powder), Supergreens (meal replacement powder), or cycling between all three.

I'm certainly not saying that you need to pop all of the pills above on a daily basis, but if your goals are building strength as quickly as possible, or muscle/strength is a limiter for you, I recommend you at least stack most of these items on your strength training days, especially if you are vegan or vegetarian.

—————————————–

Gear For Strength

Gear For Strength

In addition to taking advantage of some of the unconventional training tactics you learned about in the last chapter, such as hanging a pull-up bar in your house for greasing the groove, or including daily doses of isometrics, you definitely need to have heavy stuff around for building significant strength. This would include elements such as:

-Free weights like barbells and dumbbells and kettlebells.

-Unconventional training tools such as sandbags, tires, a strength sled, clubs and battle ropes.

-Access to a gym with strength training machines such as Nautilus, Hammer Strength and other tools that make strength training movements easier to learn, especially for beginners.

But I'm also all about making things convenient, so I have a small closet in my office which I’ve managed to stuff an entire home gym into, all for about $200. This allows me to do quick muscle building or maintenance workouts at the drop of a hat. Here is what I have in my office gym:

- 2 Dumbbells – for presses, curls, squats, and deadlifts. In addition, one very useful and space-saving piece of equipment is a set of adjustable dumbbells, which allow you to adjust a single dumbbell from 5 pounds to more than 50 pounds. You adjust these by simply pushing a pin into the weight that you desire, then taking the dumbbells off their stand. These are perfect for a small home gym, office, or even a personal training studio with limited space.

- 1 Gymstick – The Gymstick is a portable, lightweight bar with elastic tubing attached. It can be used for a portable or home full body workout. It is comprised of a fiberglass tube, a soft foam hand grip, a pair of latex rubber resistance tubes with durable fabric loops at both ends, and a rubber stopper at both ends of the stick for attaching the exercise band. You can get these in resistances up to 80 pounds, which is enough for many folks to build good strength.

- 1 Perfirmer set – the Perfirmer is a pair of special handles for push-ups that allow you to do some pretty tough variations of push-ups with portable, space-saving equipment. It has wheels and a revolving handle that allows the base to use two functioning surfaces. One side of the base provides four-wheeled construction. The opposite side of the handle is a non-slip base. This unique revolving feature allows you to utilize a variety of advanced muscle-building exercises.These are also good for building balance and mobility.

- 1 FIT10 – The FIT10 is an easy-to-use fitness trainer that only requires a door – making it perfect for quick and highly effective home, office or hotel workouts. With adjustable resistance levels for all fitness types, it can be used for upper body, abdominal, running/sprinting workouts, and an unlimited number of other exercises. It is also very good for people who need low impact exercise, since the FIT10 workout builds tremendous strength without compressing the spine, or over-stressing the joints.

- 1 Suspension Trainer – This is an essential piece of strength-training travel equipment for me. The angle of the body changes the resistance for every inch you step forward or back – offering the ability to increase or decrease your challenge, intensity, and the impact on your joints. If push-ups come easy to you, you can easily put your feet in the straps and do a multi-joint, core-challenging combo exercise. If you do not yet have the upper body and core strength to do a traditional or horizontal push-up, you can do a standing incline push-up, decreasing the pressure on your joints. As you get stronger, you can change your angle to challenge yourself more. Of course, you can also do single leg squats, rows, curls, extensions and more.

- 1 Yoga Mat – so I don’t sweat on my office floor, which is carpeted.

Sure, you could join a health club or have a fancy gym built at your house, but having this simple and cheap exercise equipment only a few feet away from your workstation vastly increases your chances of squeezing in a quick strength workout in here and there even when you don't have time to go to the gym.

—————————————–

Summary:

Strength, power, speed, balance and mobility are absolutely essential if you want your body to last for a long time – but most endurance athletes who can pound the pavement for two hours can't even do a single flawless rep of a one-legged squat, a turkish get-up or a lateral lunge…can you?

As we go through the next commonly neglected essential elements, power and speed, you'll continue to learn exactly how to put together a body that is built for the ultimate combination of health and performance.

But in the meantime, leave your questions, comments and feedback below, and don't forget to check out audio, video, slides and take-away notes from the “Become Superhuman” live event.

——————————————–

Links To Previous Chapters of “Beyond Training: Mastering Endurance, Health & Life”

Part 1 – Introduction

-Part 1 – Preface: Are Endurance Sports Unhealthy?

-Part 1 – Chapter 1: How I Went From Overtraining And Eating Bags Of 39 Cent Hamburgers To Detoxing My Body And Doing Sub-10 Hour Ironman Triathlons With Less Than 10 Hours Of Training Per Week.

-Part 1 – Chapter 2: A Tale Of Two Triathletes – Can Endurance Exercise Make You Age Faster?

Part 2 – Training

-Part 2 – Chapter 1: Everything You Need To Know About How Heart Rate Zones Work

-Part 2 – Chapter 2: The Two Best Ways To Build Endurance As Fast As Possible (Without Destroying Your Body) – Part 1

-Part 2 – Chapter 2: The Two Best Ways To Build Endurance As Fast As Possible (Without Destroying Your Body) – Part 2

-Part 2 – Chapter 3: Underground Training Tactics For Enhancing Endurance – Part 1

-Part 2 – Chapter 3: Underground Training Tactics For Enhancing Endurance – Part 2

-Part 2 – Chapter 4: The 5 Essential Elements of An Endurance Training Program That Most Athletes Neglect – Part 1: Strength

Coming in Part 3 – Recovery…

-Importance of when training adaptations actually occur (during the rest and recovery period) and show how to recover with lightning speed, including every beginner-to-advanced method such as ice, cold laser, PEMF, compression, electrostim, grounding, earthing, cold-hot contrast, ultrasound, etc…

-All about overtraining and exactly how to identify it, avoid it, and bounce back from it as quickly as possible, including a focus on self quantification methods such as heart rate variability and pulse oximetry, and biomarker testing for hormones, vitamins, minerals, etc…

-Beginner-to-advanced stress relief techniques, relaxation and sleep techniques for both home, as well as for traveling – including managing late nights, loss of sleep, napping, jetlag, etc.

-Advanced sleep-hacking methods using artificial light mitigation, binaural beats, etc…

-And much more!

————————————

References (more references coming soon):

1. Adrian, E. (1914). The all-or-none principle in nerve. Journal of Strength and Physiology, 47(6), 460-74.

2. Beekley, M., Abe, T., Kondo, M., Midorikawa, T. and Yamauchi. T. (2006) Comparison of normalized maximum aerobic capacity and body composition of sumo wrestlers to athletes in combat and other sports. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine CSSI, 13-20.

3. Chapman, D. (2006). Greater muscle damage induced by fast versus slow velocity eccentric exercise. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 27(8), 591-8.

4. Crewther, B. (2011). Two emerging concepts for elite athletes: the short-term effects of testosterone and cortisol on the neuromuscular system and the dose-response training role of these endogenous hormones. Sport Medicine, 41(2), 103-23.

5. Frank, K. (2013, April 30). Examine.com. Retrieved from http://examine.com/

6. Harrison, D. (2009). Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature, 460(July), 392-95.

7. Huffington Post. (2012, 08 06). Olympic trainer Rob Schwartz on what it takes to train for the olympics. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/08/06/olympic-trainer-rob-schwartz_n_1746429.html

8. Hurn, M. (2012). A day in the life of.. an olympic swimmer. Retrieved from http://www.weightwatchers.com/util/art/index_art.aspx?tabnum=1&art_id=111291&sc=3010

9. Jones, T. (2013). Performance and neuromuscular adaptations following differing ratios of concurrent strength and endurance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, March(13), Epub

10. MacNamara, J. (2012). Effect of concurrent training, flexible nonlinear periodization, and maximal effort cycling on strength and power r-340011. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, October(3), Epub.

11. Meredith, C. (1989). Dietary protein requirements and body protein metabolism in endurance-trained men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 66(6), 2850-6.

12. Miles, M. (1994). Exercise-induced muscle pain, soreness, and cramps. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 34(3), 203-16.

13. Murphy, A. (2013). The effect of post-match alcohol ingestion on recovery from competitive rugby league matches. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(5), 1304-12.

14. Newton, M. (2008). Comparison of responses to strenuous eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors between resistance-trained and untrained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(2), 597-607.

15. Obayashi, H. (2012). Effects of respiratory-muscle exercise on spinal curvature. Journal of Sports Rehabilitation, 21(1), 63-8.

16. Quatman-Yates, C. (2013). A longitudinal evaluation of maturational effects on lower extremity strength in female adolescent athletes. Pediatric Physical Therapy, April(24) Epub.

17. Ra, S. (2013). Additional effects of taurine on the benefits of bcaa intake for the delayed-onset muscle soreness and muscle damage induced by high-intensity eccentric exercise. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, (776), 179-87.

18. Salvadego, D. (2013). Skeletal muscle oxidative function in vivo and ex vivo in athletes with marked hypertrophy from resistance training. Jounral of Applied Physiology, March(21), Epub.

19. Tarnopolsky, M. (1988). Influence of protein intake and training status on nitrogen balance and lean body mass. Journal of Applied Physology, 64(1), 187-93.

20. Tremblay, M. (2004). Effect of training status and exercise mode on endogenous steroid hormones in men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 96(2), 531-9.

21. Vogler, E. (2012). Protein adsorption in three dimensions. Biomaterials, 33(5), 1201-37.

22. Wilson, J., & Wilson, G. (2006). Contemporary issues in protein requirements and consumption for resistance trained athletes. International Journal of Sociology and Sports Nutrition, 3(1), 7-27.

Hi Ben,

i currently take a group of 4 endurance athletes through a strength every Wednesday. I live in New Zealand so it is approaching winter. I work on the basis of a 6 week cycle culminating in the 3 rep max test to have a marker in the place. I tend to pyramid sets when they are going squats, so set 1 would be 15 reps, set 2 would be 12 reps and set 3 be 10 reps. Is this a good approach mixing strength endurance with hypertrophy training? Is decreasing the reps the reps and loads going to build a better strength base. Is there something i am missing? I know this not entirely to what you put out. Also half the group are female, so i have to be careful with the approach with them.

I look forward to your reply.

When you are talking about intensity do you mean percent of 1rm? Or is that just basically how hard it feels for you?

Depends. You can rank intensity based on RPE, speed, heart rate, percentage of 1RM, etc. More than one way to skin that cat!

I’m wondering about rep ranges. There’s the traditional high rep in the 10-12 range, low weight to build endurance. However, recently I’ve been reading articles that talk about low rep, high set scheme using a heavy weight. For example back squat 2 reps, 20 sets at 85%+ of 1RM. Thoughts?

I cover this here: https://bengreenfieldfitness.com/2015/06/stren…

Thank you! The podcast is awesome, so are exos aminos!

Has the RDA of protein been updated to match the protein absorption rates of certain foods; those values are very vague. For example, protein powder’s absorption rate is around 30% less than eggs.

Ben,

What is your opinion of high intensity training i.e. doing one set to failure during the offseason?

It's a decent strategy anytime of the year. I wouldn't do it every single day but mixing it in is fine.

If I'm following the approach that is specified in Body by Science by McGuff and also incorporating HIIT (the day after the weight training to failure session), should I be worried about the HIIT interfering with recovery since he recommends around 7 days off?

I'd need to know a little bit more about the exact Body By Science approach you're using…but generally that type of recovery period refers to strength, not cardio (i.e. HIIT)

I was primarily talking about the “Big Five” workout once a week: row, chest press, pull-down, overhead press, and leg press. Each of these done with one set of 10 to 20 second reps until failure. The cardio differentiation makes sense though. In my case, I’m thinking I would need to cut back on my daily one-hour bike commute with many hills. It does leave my legs sore. Thank again, Ben!

I wondered about the harm in completing fasted strength training workouts. I typically do 25-30 minutes of fasted strength training twice per week in the morning because it’s the only time I have available to work out. Is this harmful?

Thank you,

Jennifer

Depends on your goals. If you're trying to BUILD MUSCLE then yes. If these aren't marathon-esque 90+ minute strength training sessions, you're fine. Especially if you're having breakfast after.

Great chapter, strength training is not only an important aspect of endurance training,but also being able to live a long, healthy and enjoyable life.

I would be so interested in hearing what your recommendations are for a female college athlete (volleyball) who does feel over trained and showing symptoms of estrogen dominance or elevated cortisol. She has not much of a choice as far as training and practicing unless she wants to get cut from the team. Have you done any podcasts or articles on athletes that aren't allowed to cut back on training for this reason ?

This is a tough one, because you're obligated to train OR get cut from the team. If I were in your situation I would be doing the one thing that above anything else reduces risk of amenorrhea and hormonal mileiu in female athletes: stuffing your face. That's right: I'd be eating everything in sight. Granted, I'd still be eating HEALTHY foods like olive oil, avocados, raw milks and yogurts, coldwater fish, grassfed beef, etc. but you should be eating lots. Never going hungry. I can help MUCH more specifically here: http://pacificfit.net/items/one-on-one-consultati…

Ben, another pretty good chapter, thanks !

looking forward fort the upcoming parts 2 and 3. little by little doing the shift

have a great week !

Ben.. Good stuff.. Any easy way to measure nitrogen balance in house?? Thank you so much for all the free info .

Not really. But you could get a metametrix ion panel and look at amino acids: http://www.metametrix.com/files/test-menu/interpr…

Doubles:

"So how much how much strength or muscle do you actually need for endurance sports?"

"In the endurance athletes, it was found that found that aerobic capacity peaks out"

Another great chapter! I asked another full question that I had typed and then hit enter without my name, so it got erased…! But I'll send them to the podcast Q&A. They mostly regard lifting and getting strong, how to lift often (as I enjoy it), doing triathlons… and still being shredded!

Thanks Chuck!

Awesome chapter! I was curious, what is your opinion on specific strength workouts? Like overgear workouts, or we do single stick workouts for skiing all the time

What is an overgear workout?

My old coach made us do these all the time. Overgear workouts are where you put your bike in a big gear (like 53×17 or something) and go up a hill mashing the gear at around 50-60rpm to build leg “specific strength”. We would do either quick efforts of 20-40pedal strokes or longer 4min efforts. I’ve always wondered about that type of workout; it can’t be too great on knees but it seemed to help a little as far as strength. But I suppose the longer efforts were just glorified threshold training with a low cadence because we were told to never go out of zone 3 for the efforts.

Yes, those are like the "underspeed" workouts I talked about in the previous chapter!

Another great chapter. Curious about why you primarily recommend beta alanine as a pre-workout when the scientific studies are usually based on total daily intake. Don't get me wrong, i try to time it as a pre-workout but today is a day off for me and i'm doing three 2g doses (spaced at least two hours apart).

What do you mean? I have beta-alanine in there….

Thanks Ben great stuff as always.

Love your citruline / Beta Alan / Amino stack before exercise as is kind of funny been using that mix myself and always made me feel like a skin tingly beast mode machine before boxing or weight lifting or running!

So many people, including me, sometimes just end up exclusively training the one aspect of fitness they are in love with at the time and neglect the others to their detriment. I have been sidelined a few times to injuries due to my neglect of simple things like stretching… (Piriformis syndrome so bad I could not sit for 6 months…)

Glad you liked it Danny. And yes, that's a pretty potent stack!